Black women in the US have higher fertility than White women, but this difference does not emerge consistently at all educational levels. Emma Zang and Aparajita Kaphle document these education-specific differences and discuss some of their possible causes.

Black women in the United States have always had higher fertility, on average, than White women. In 1990, for instance, total fertility rates (TFRs) were about 2.5 and 1.8 children per woman, respectively, for Blacks and Whites, and although levels have declined for the former (down to about 1.9 in 2012), the ranking has consistently remained the same over the years (Sweeney and Raley 2014).

The role of education

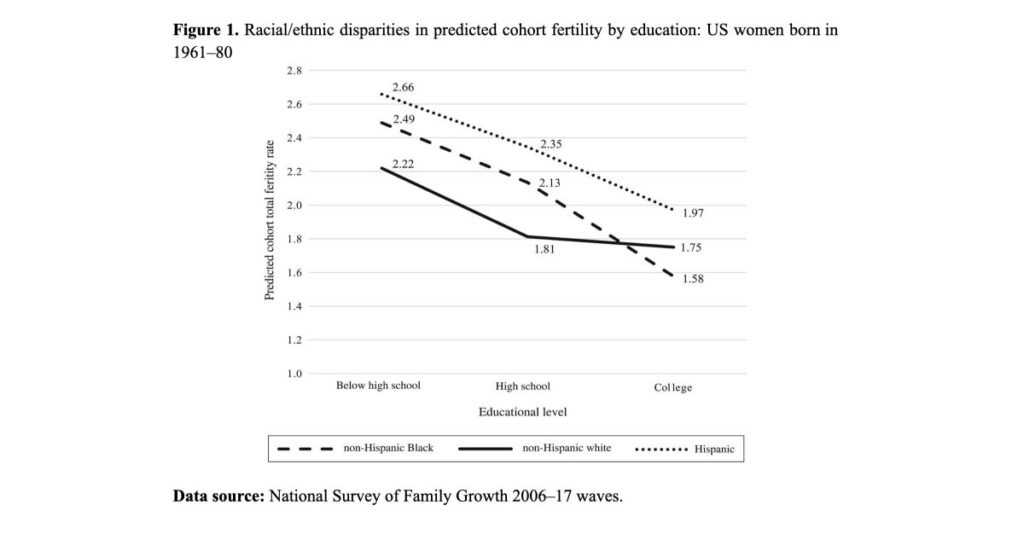

This, however, depends also on the differential educational attainment of the two ethnic groups (Zang, Sariego and Krishnan 2022). Let us consider the birth cohorts of 1961–80: based on data from the National Survey of Family Growth (2006–17 waves), among women with educational levels below high-school, Hispanic women have the highest fertility (2.66), followed by Black women (2.49) and then White women (2.22) (Figure 1), with disparities that may be partially explained by some known cultural and socio-economic influences. The latter, for instance, pose challenges for minority groups in accessing adequate healthcare and contraception, especially less-educated Blacks and Hispanics. Hispanics’ higher fertility has long been attributed to their “familism” (Marin and Vanoss Marin 1991), whose importance, however, has been subsequently downplayed (Hartnett and Parrado 2012). Other explanations include a mix of wanted and unwanted pregnancy stemming from both systemic barriers to healthcare as well as cultural norms that encourage having more children (Hartnett 2014).

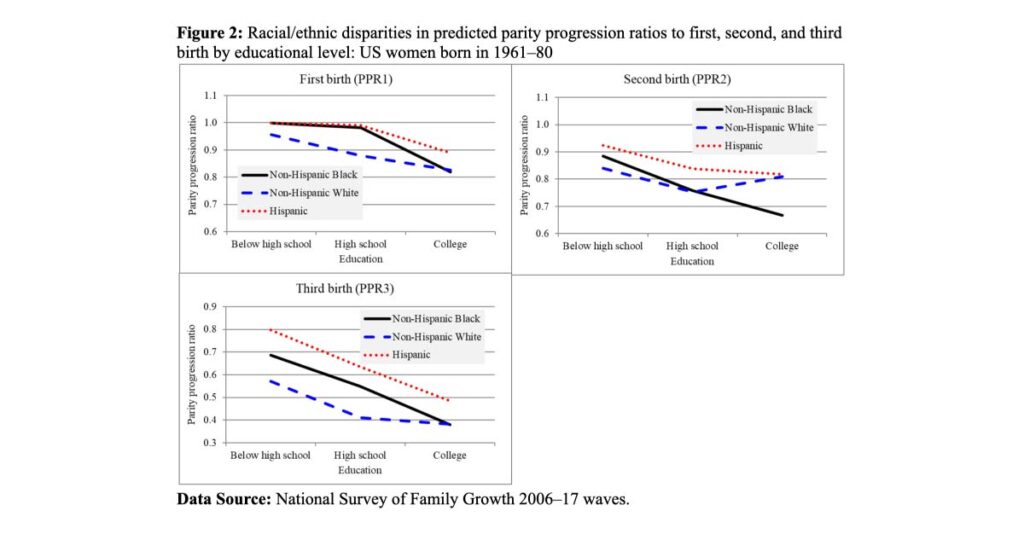

By contrast, among women with college degrees, while Hispanic women still have the highest fertility (1.97), White women have more children than Black women (TFR = 1.75 and 1.58, respectively), because the latter transition less frequently to a second child (Figure 2).

Explaining the differences

What causes this difference? An exploration into Black motherhood would require a comprehensive examination of the several elements that affect families and family planning, including healthcare, employment, and limited access to resources.

Take childcare support, for instance. Educated White women may have greater opportunities to pay for, and outsource, childcare labor, a luxury that may not be as accessible to Black women.

But the single most important element is probably the pervasive discrimination experienced by highly educated Black women, which increases the challenges they face, and may affect various facets of their life, including health and fertility (Tipre and Carson 2022). Racism, colorism and sexism in the workplace are still strong in the United States (Showunmi 2023), and, among other things, they can be a deterrent against having more children.

Conclusions

In short, it is important to delve deeper and explore the impact of structural barriers that Black women face, both low and highly educated. These barriers, we discussed in this article, also affect their fertility.

In all cases, these findings highlight that fertility differences across racial/ethnic groups cannot be solely attributed to race/ethnicity. Fertility rates are influenced by a complex interplay of factors such as socioeconomic status, educational attainment, access to healthcare, cultural norms, and individual choices. Generalizations about fertility rates based solely on race can perpetuate stereotypes and overlook the significant diversity within racial and ethnic groups.

References

- Hartnett C.S. (2014) White-Hispanic differences in meeting lifetime fertility intentions in the U.S. Demographic Research, 30(43):1245-1276. DOI: 10.4054/DemRes.2014.30.43.

- Hartnett C.S., Parrado E.A. (2012) Hispanic Familism Reconsidered: Ethnic Differences in the Perceived Value of Children and Fertility Intentions. The Sociological Quarterly, 53(4): 636-653, DOI: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2012.01252.x

- Marin, G., Vanoss Marin B. (1991) Research with Hispanic populations. Sage Publications, Inc.

- Showunmi V. (2023). Visible, invisible: Black women in higher education. Frontiers in Sociology, 8, 974617. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2023.974617

- Sweeney M.M., Raley R.K. (2014). Race, Ethnicity, and the Changing Context of Childbearing in the United States. Annual Review of Sociology, 40, 539–558. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-071913-043342

- Tipre M., Carson T.L. (2022). A Qualitative Assessment of Gender- and Race-Related Stress Among Black Women. Women’s Health Reports (New Rochelle, N.Y.), 3(1), 222–227. https://doi.org/10.1089/whr.2021.0041

- Zang E., Sariego C., Krishnan A. (2022) The interplay of race/ethnicity and education in fertility patterns. Population Studies, 76(3): 363-385, DOI: 10.1080/00324728.2022.2130965

No comments:

Post a Comment