Children and (unequal) sharing of housework between partners in Hungary

January 23, 2023 Zsuzsanna Veroszta

In addition to their childcare responsibilities, women with young children often have to do more housework, thus making an already unequal balance even more skewed. Zsuzsanna Veroszta shows that, in absolute terms, the burden is greater on mothers of several children, and that the biggest relative increase occurs after the birth of the first child.

The division of housework between partners depends on the life cycle of households, including childbearing, which is perhaps the single most relevant factor (Birch et al., 2009). After giving birth, women tend to be more burdened with housework, as well as having increased childcare responsibilities. This depends partly on practical circumstances, such as maternity leave, and partly on cultural and value-related attitudes. In Hungary, studies on the division of housework within households have shown that even though their labour market participation is very high, women traditionally bear the brunt of household responsibilities (Gregor and Kováts, 2020). The prevalence of this phenomenon – also known as the ‘second shift’ (Hochschild and Machung, 1989) – depends not only on the external workload, but also on place of residence, education and age, including the age difference between partners. The number and age of the children also matters.

In a recent study, my colleagues and I analysed the amount and share of housework performed by women during pregnancy and when the child is 6 months old (Veroszta et al., 2022). The self-reported data, concerning women who cohabit with a male partner, were obtained via face-to-face interviews in the first wave (among pregnant women) and second wave (when the child was aged 6 months) of the Growing Up in Hungary – Cohort ’18 longitudinal study (2018–19).

In addition to their childcare responsibilities, women with young children often have to do more housework, thus making an already unequal balance even more skewed. Zsuzsanna Veroszta shows that, in absolute terms, the burden is greater on mothers of several children, and that the biggest relative increase occurs after the birth of the first child.

The division of housework between partners depends on the life cycle of households, including childbearing, which is perhaps the single most relevant factor (Birch et al., 2009). After giving birth, women tend to be more burdened with housework, as well as having increased childcare responsibilities. This depends partly on practical circumstances, such as maternity leave, and partly on cultural and value-related attitudes. In Hungary, studies on the division of housework within households have shown that even though their labour market participation is very high, women traditionally bear the brunt of household responsibilities (Gregor and Kováts, 2020). The prevalence of this phenomenon – also known as the ‘second shift’ (Hochschild and Machung, 1989) – depends not only on the external workload, but also on place of residence, education and age, including the age difference between partners. The number and age of the children also matters.

In a recent study, my colleagues and I analysed the amount and share of housework performed by women during pregnancy and when the child is 6 months old (Veroszta et al., 2022). The self-reported data, concerning women who cohabit with a male partner, were obtained via face-to-face interviews in the first wave (among pregnant women) and second wave (when the child was aged 6 months) of the Growing Up in Hungary – Cohort ’18 longitudinal study (2018–19).

Women’s share of domestic work increases once they have a child

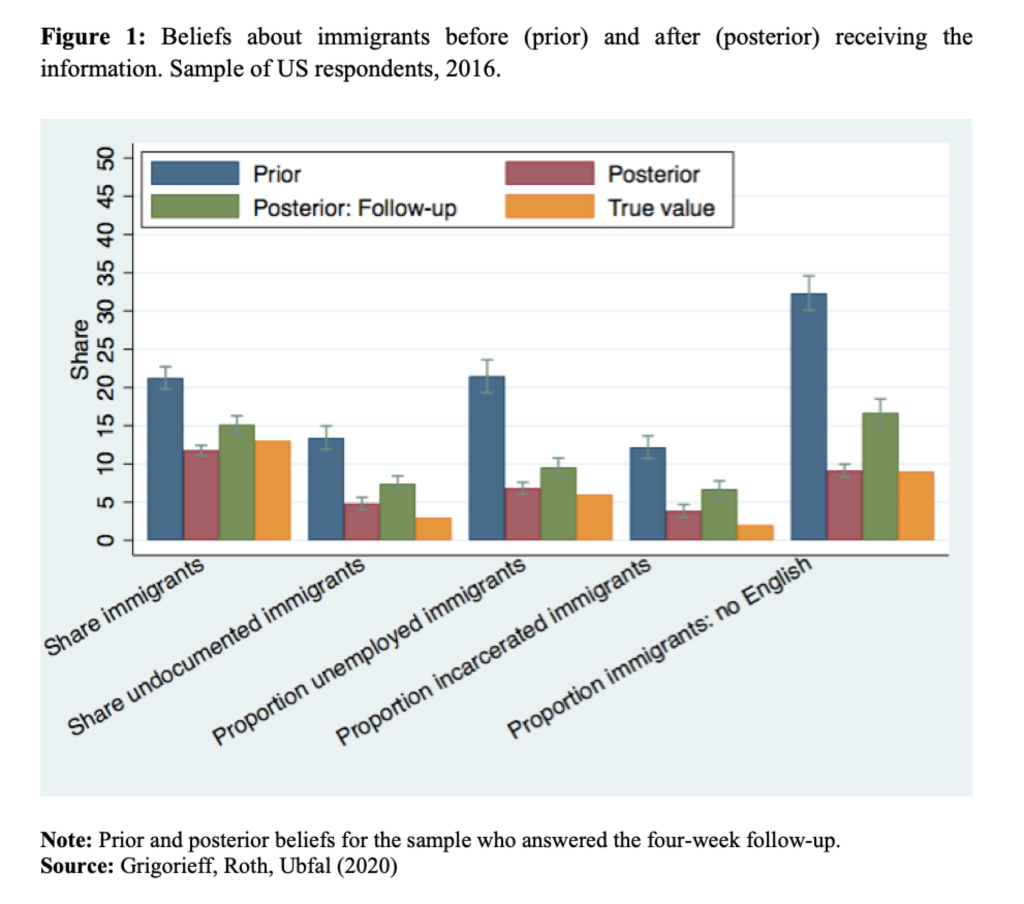

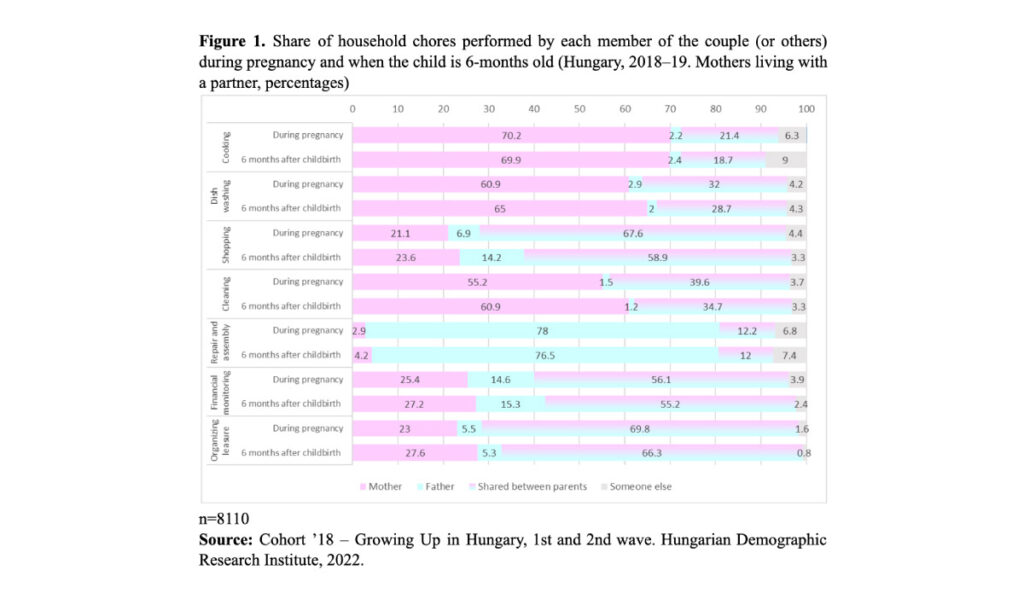

According to data from the Cohort ’18 survey, already during pregnancy, the burden of everyday domestic tasks – cooking, washing, shopping, cleaning, etc – is heavily skewed towards women. Men are most likely to do maintenance work in or around the house. The most common joint or shared activities include shopping, managing household finances and organizing leisure activities. About six months after the birth of their child, mothers seem to be doing slightly more washing and cleaning, while the number of tasks the couple do together decreases in almost all areas (Figure 1).

The more (children), the heavier (the burden of household chores)

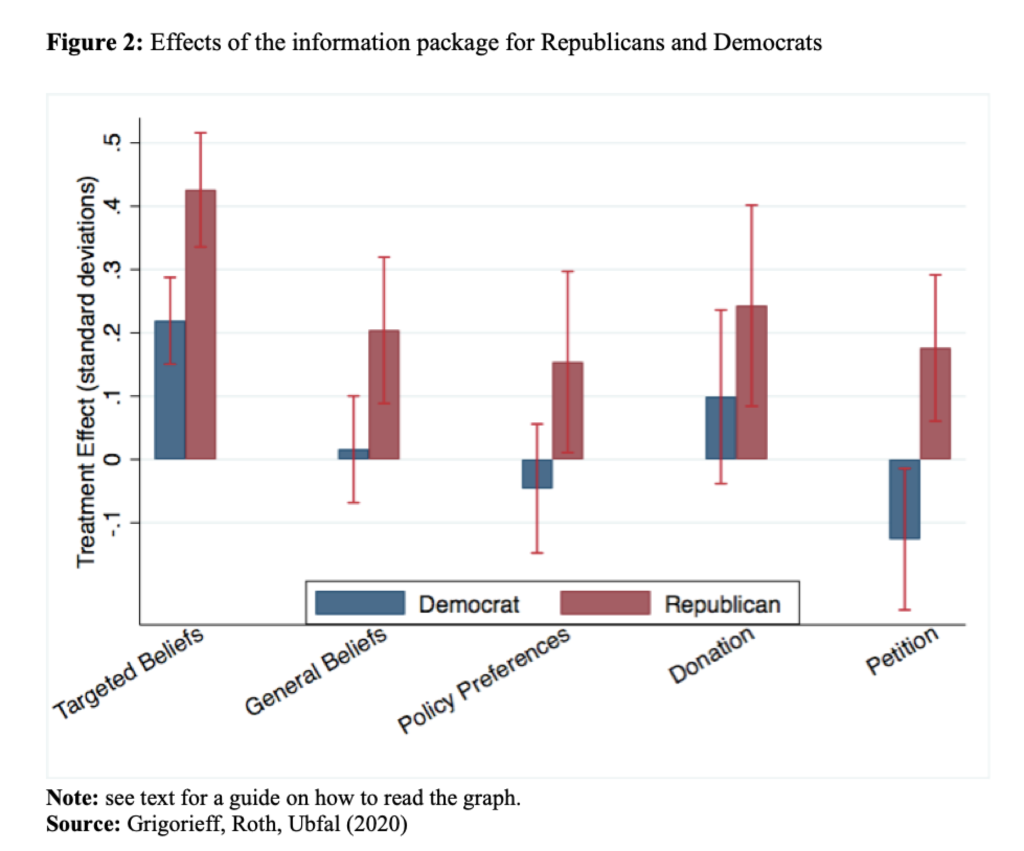

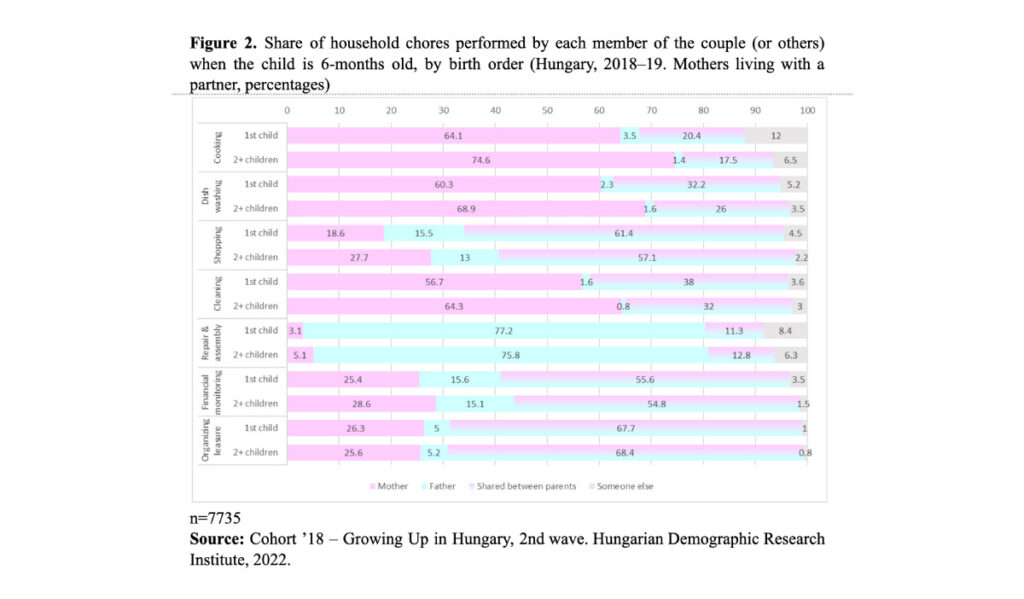

These data reflect the average Hungarian couple with a 6-month-old child. However, when this baby is not the first child in the household, the division of housework is even more heavily tilted against mothers. Not only do fathers with more children take on fewer tasks, but there is also a big reduction in shared household activities (Figure 2). It is also clear from the data that external help (whether paid or unpaid) tends to be available more to mothers of only children; with a second or third child, the mother’s household tasks tend to increase.

A larger relative increase for first-time mothers

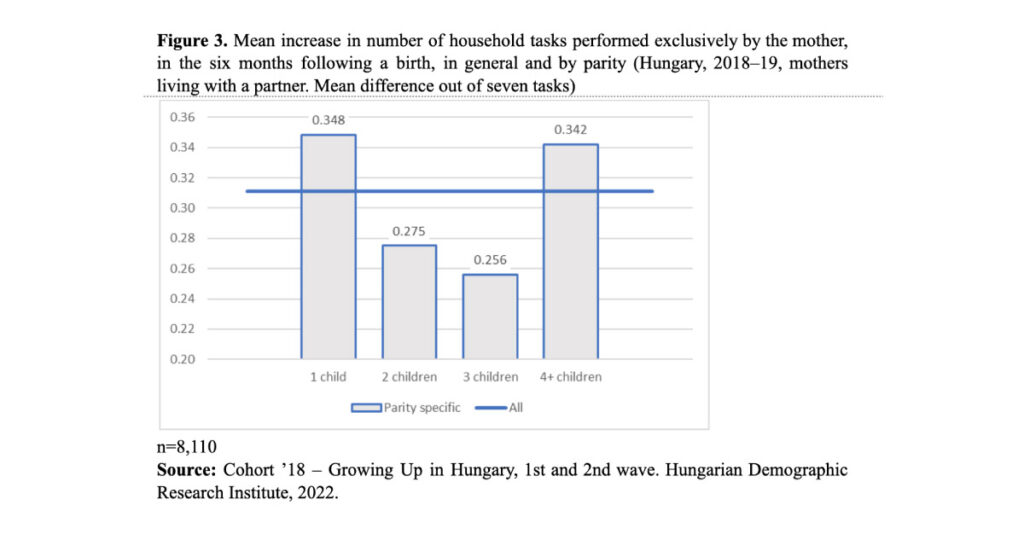

Depending on the number of children, the picture differs if we look not at the absolute number of tasks, but at the increase in tasks after the birth – i.e. the relative extent of the change. In this case, we look at the difference between the number of tasks that the mother performed before and after the birth.

On average, a pregnant woman mainly or always performs 2.4 household tasks out of 7. For those with a 6-month-old child, the average is higher: 2.75 tasks. Comparing the two periods, in more than 40 per cent of cases, the number of household tasks performed by the woman increases in the 6 months following the birth, typically by one or two extra household jobs.

Breaking the data down by parity, we find, not surprisingly, that mothers with more children do most of the housework in absolute terms. However, the relative increase in the number of tasks is smaller for them – with the exception of families with four children or more, where both the absolute and the relative burden on mothers increases significantly with the arrival of a new child. Housework increases more for women who are at home after the birth of their first child.

In short, in Hungary at least, having additional children increases women’s household workload in general, but it is after the first birth that the balance of housework between partners tilts most strongly against women.

References

- Birch, E.R., Lee, A.T. and Miller, P.W. (2009): Household Divisions of Labour: Teamwork, gender and time. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gregor, A. and Kováts, E. (2020): Work–life: balance? Tensions between care and paid work in the lives of Hungarian women. Socio.hu Társadalomtudományi Szemle, 9(SI7), 91–115.

- Hochschild, A.R. and Machung, A. (1989): The Second Shift: Working parents and the revolution at home. Viking.

- Veroszta, Zs., Boros, J., Kapitány, B. et al. (2022): Infancy in Hungary. Report on the Second Wave of Cohort ’18 – Growing Up in Hungary. Working Papers on Population, Family and Welfare, No. 40. Hungarian Demographic Research Institute, Budapest.