How pandemics allow us to understand why our ancestors were stuck in poverty

Our World in Data presents the data and research to make progress against the world’s largest problems.

This post draws on data and research discussed in our entries on Economic Growth and Poverty.

Poor material living conditions were such a persistent and pervasive reality that, for much of human history, it was unimaginable that it could ever be different.

Poverty did not change and so it was easy to believe that poverty was unchangeable. The Reverend Thomas Malthus wrote about the living conditions in his native England “It has appeared that from the inevitable laws of our nature, some human beings must suffer from want. These are the unhappy persons who, in the great lottery of life, have drawn a blank.”1

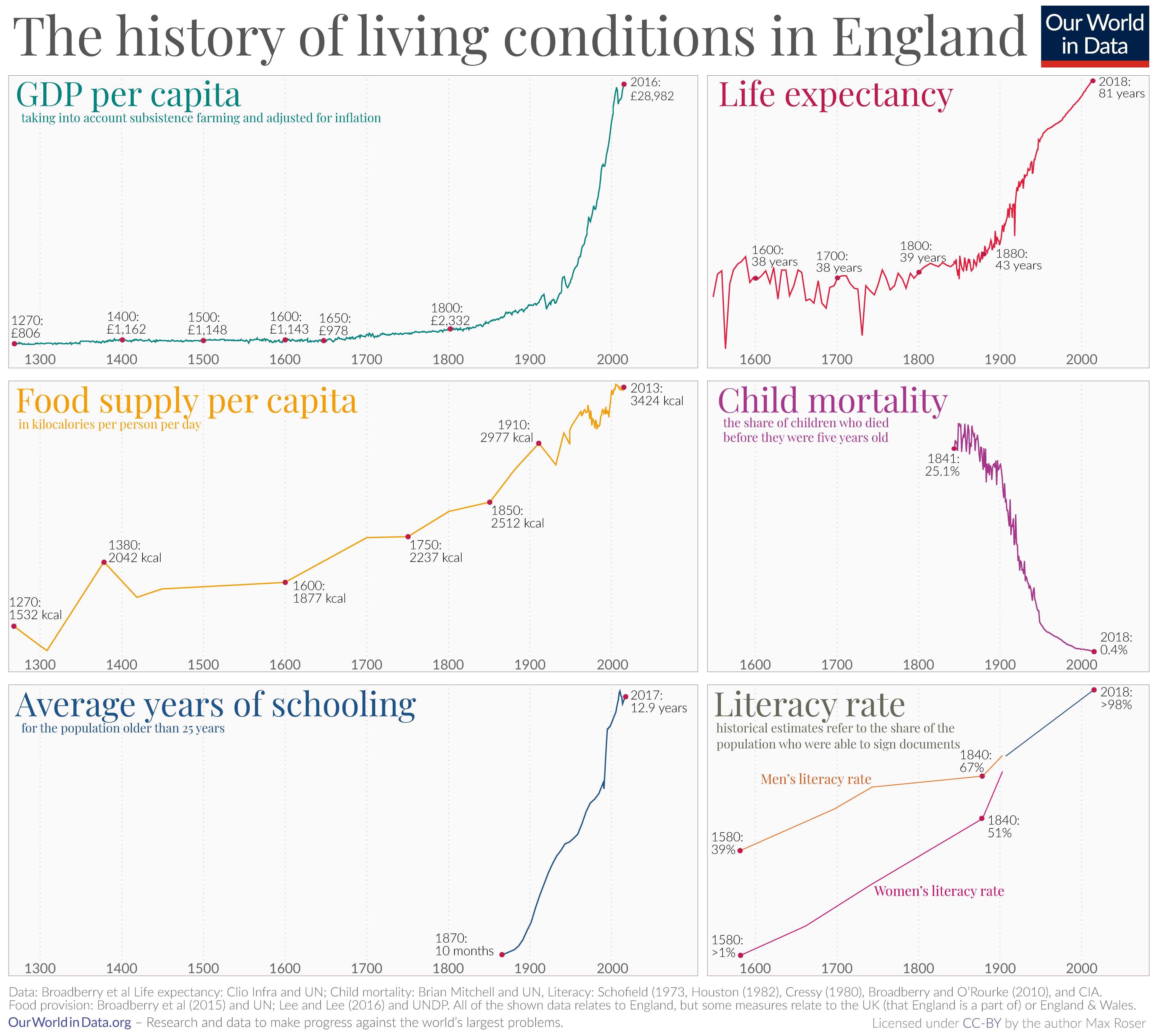

Reconstructions of living conditions over the long-run suggest that when Malthus wrote these words in 1789 he was right about the past. As the visualization here shows, GDP per capita – the average income of people – had remained extremely low.

But Malthus turned out to be very wrong about the world’s reality after his death: In the two centuries since his death many countries broke out of the stagnation of the past, achieved economic growth, and reduced poverty.

Why is this? Why were our ancestors stuck in poverty for so long?

Economic growth today is achieved when economies become more productive – productivity can increase due to new technologies (a farmer with a tractor is more productive than a farmer with an ox; a cargo ship is more productive in delivering goods than a horse buggy; and a factory with power looms is more productive in making the clothes you are wearing than a weaver working by himself) and productivity can increase through social and economic changes (trade makes it possible to grow food where agricultural productivity is high and better education and literacy makes it possible for people to become more productive at their jobs).

In the past our ancestors also achieved productivity increases, but – as we will see – this didn’t lead to better living standards but to more people.

Understanding this mechanism – called the Malthusian Trap – allows us to understand why our ancestors remained in poverty and it explains why sustained economic growth, where the material living conditions of a population increases over several generations, was not achieved until just a few generations ago.2

England was the first country to achieve sustained growth, and is also a country for which historians have produced very careful reconstructions. For both of these reasons, England is the country we will look at in detail.

The careful reconstructions of economic historians, including detailed accounts of what was produced and consumed through the centuries, allow us to understand the dynamics of poverty and prosperity in the past. For GDP per capita to capture people’s living conditions historians assign a monetary value to the goods and services that people consumed. This is crucial because it means that historians take into account that people lived off products and services that were not bought and sold in the market, which importantly often includes their own production.3

And it wasn’t only GDP per capita, living standards remained poor by many metrics as the chart below on the history of living conditions in England shows. Life expectancy fluctuated up and down at around 40 years without a trend, access to education and literacy were poor, child deaths were very common, and food supply remained extremely poor during these centuries.

The chart here zooms into the economic history of medieval England from 1270 to 1660.4 Although these 400 years are only a fraction of humanity’s long history, they allow us to understand the mechanism that for so long trapped our ancestors in poor material living conditions.

The ups and downs in the medieval economy are small when compared with the rise in prosperity since then, but it is clear that, in the context of their time, these were significant changes.

Most prominently we see that very suddenly, in the middle of the 14th century, incomes jumped up to a substantially higher level. Until the mid-1340s the English lived on around £800 per year; but then, in a period of less than five years, incomes increased to over £1000. Prosperity kept on increasing so that by the end of the century they reached a new plateau at close to £1,200 per year. Within half a century the English saw their incomes increase by almost 50%.

This rise in prosperity happened during some of the most terrible decades in English history. In June 1348 the plague arrived in England and it quickly became a pandemic of enormous dimensions that ravaged the entire island: It is estimated that in the three years after 1348 the population of the country declined from 4.8 million to 2.6 million. Almost half of the English population died.5

The devastation caused by the Black Death was so large that it is clearly visible in our reconstructions of the long-run development of the world population.

Why did one of the very worst pandemics the world has ever seen coincide with a rise in living standards?

No comments:

Post a Comment