The future of the Italian population depends in large part on migration. Marcantonio Caltabiano and Gianpiero Dalla-Zuanna compare the most recent forecasts of net migration for Italy proposed by Eurostat, ISTAT and the Population Division of the United Nations. Depending on assumptions, the virtually inevitable demographic decline of Italy may be profound or just modest: the latter scenario, however, seems to be more likely.

Italy’s demography is alarming. In 2022, births reached their historical minimum of 393,000, 141,000 fewer than only ten years before, and deaths outnumbered births by 320,000. According to ISTAT (Italian National Statistical Institute), after reaching a maximum of 60.3 million in 2014, the Italian population has been decreasing for almost a decade, falling below 59 million at the beginning of 2023. The outlook on the age imbalance is even more worrying. Without migration, between 2023 and 2042, some 10 million people will turn 20 (those born over the period 2003-2022, 500,000 a year on average) and some 18 million will turn 65 (the baby-boomers, born over the period 1958-1977). Good news for young job seekers? Possibly, but while many new retirees have a maximum of 8-10 years of schooling, a large share of the new labour market entrants will hold a high school diploma or a university degree, with 13-18 years of schooling, which means that youth unemployment may coexist with job vacancies. The Italian labour market (mainly based on manufacturing and tourism), the welfare system and society as a whole will struggle to cope with such a drain on the potential workforce, and the consequences of this structural change.

These data have received wide coverage in the international press and on social media. Paradigmatic is Elon Musk’s tweet of April 7, 2023, viewed by 5.3 million people: Italy is disappearing! Is it an inescapable destiny? To discuss these issues, we compare three population forecasts, proposed respectively by the Population Division of the United Nations – UN DESA (2022), ISTAT (2022), and the Statistical Office of the European Union – Eurostat (2023).

Comparing scenarios

Migration is difficult to predict. Movements to and from other countries are influenced not only by individual choices and the economic situation, but also by the migration policies of both origin and destination countries, and by geopolitical factors, whose impact in the short and long term is not easy to evaluate. Furthermore, existing data, on which forecasts are built, may be of poor quality and insufficiently detailed (e.g. by sex and age).

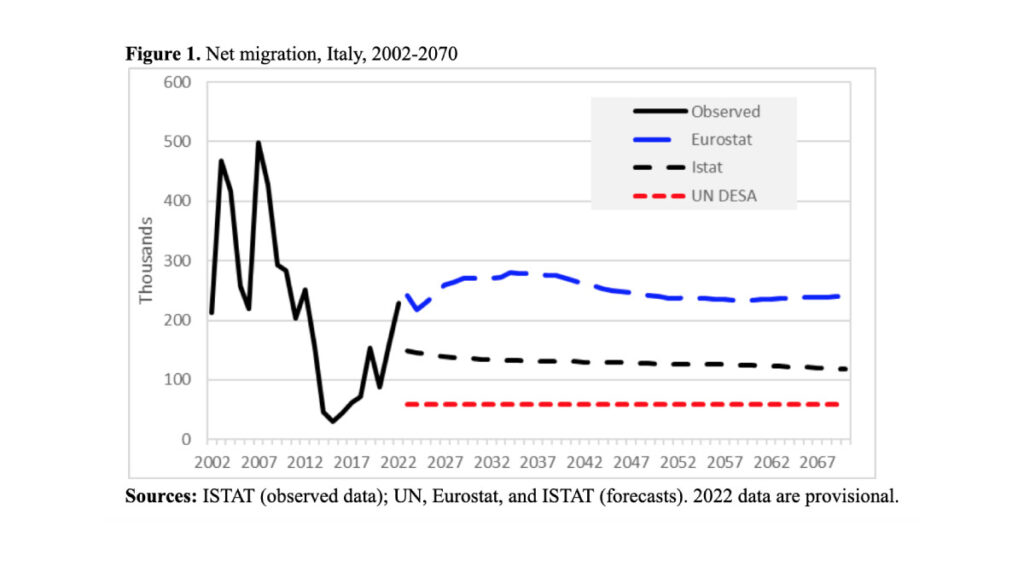

In Italy, immigration appears to have been extremely variable in the past 20 years or so, but this variability probably reflects the administrative nature of the data, influenced by such events as regulatory changes (for example regularization of foreigners already living in the country), entry into the European Union of other states (e.g., Romania), political and economic crises in neighbouring countries, and so on (Figure 1, left-hand side).

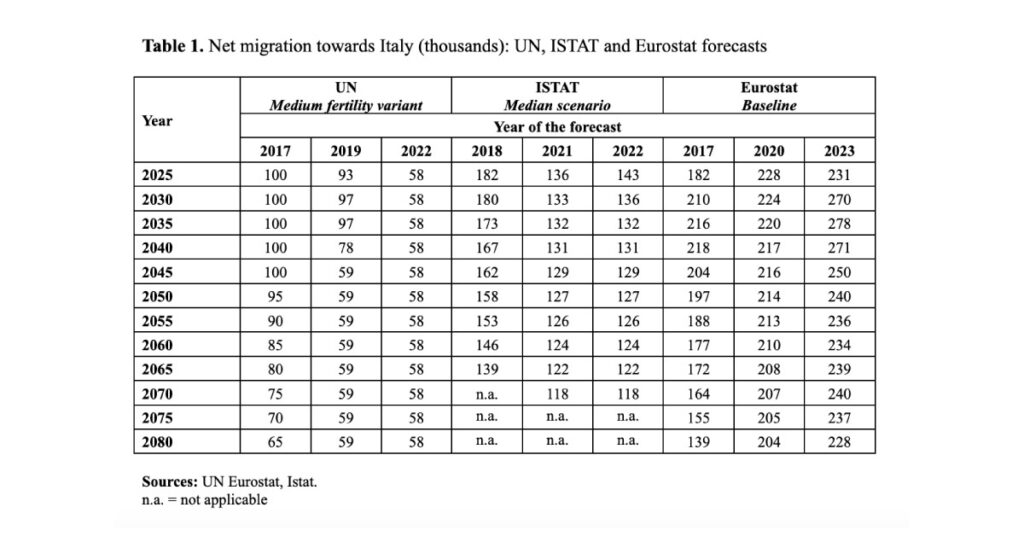

Predicted levels of net migration for the period 2025-2080 vary considerably depending on the agency that produces them (Figure 1, right-hand side, and Table 1). Everybody agrees that there will (probably) be positive net migration, but the UN estimates are much lower than the other two. Furthermore, previous UN exercises (2017 and 2019) projected declining net migration, while their latest (2022) projections assume that it will remain constant throughout the period (at initially lower levels). Eurostat forecasts significantly higher net migration (and higher than in their previous forecasts), with a moderate decline over time. Finally, the ISTAT forecast is halfway between the other two, lower than in preceding versions of analogous exercises, especially in the first years.

These large differences are due to variations in the underlying assumptions. The UN predicts constant net migration over time, close to the mean of the period preceding the COVID-19 pandemic, taking into account government policies and the flows of irregular immigrants and refugees, and assuming that two-thirds of those who immigrate will return home within five years of arrival.

The methodology behind the most recent (2023) Eurostat forecasts has not been published yet, but will likely resemble that of previous publications (of 2017 and 2020), based on the attraction factor due to the decline in the active population (WAFM – Working-Age Feedback Mechanism).

The ISTAT forecast was based on the opinions of 86 experts recruited among participants at the 2019 conference of the Italian Association for Population Studies (AISP) who were asked to estimate immigration and emigration for 2050 and 2080. The probabilistic model used for the forecast was developed using the distribution of figures these experts provided. (For more details, see the references.)

Consequences for the size and structure of the Italian population

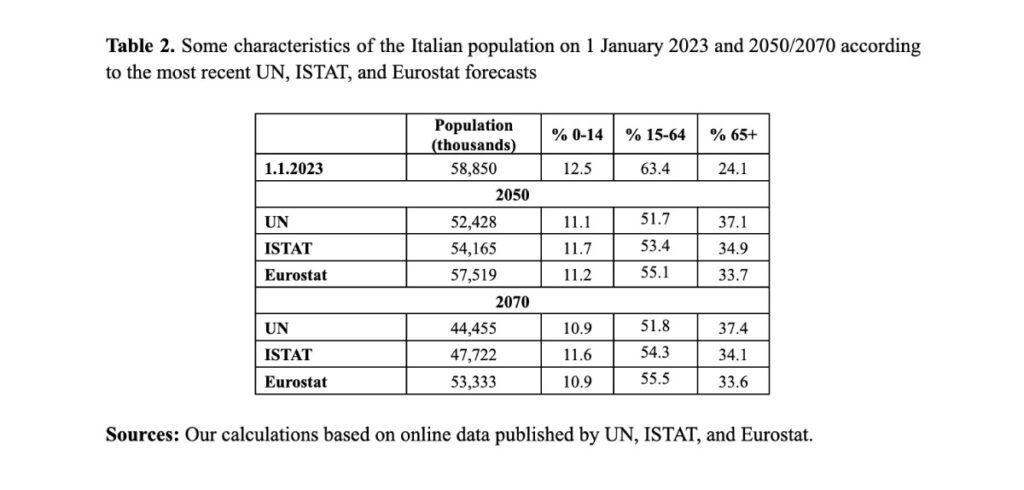

Different net migration hypotheses generate different patterns of Italian population change over the century. In Table 2, we compare the projections to 2050 and 2070. The Italian population is likely to decline in the next 50 years, but in markedly different ways in the three scenarios. From the 59 million estimated by ISTAT on 1 January 2023, it may fall to just 44 million in 2070 (–14 million) according to the UN, or to 53 million, if one believes Eurostat (–5 million), while the proportion of people aged 65 years and over fluctuates between 34% (Eurostat) and 37% (UN). Differences are smaller for young people (below 15 years) because this component is mainly affected by future fertility trends, for which the three institutions apply similar hypotheses (only slightly higher for ISTAT). Finally, the adult population will drop by about ten percentage points (somewhat less according to Eurostat, somewhat more according to the UN), tending to stabilize after 2050 due to the extinction of the baby-boomers. By 2050, the absolute size of the population aged 15-64 years is very different in the three forecasts, ranging between 27 million (UN) and 32 million (Eurostat). This represents a decline in all cases, considering that the current (2023) number is about 37 million.

What will really happen?

According to the forecasts presented here, Italian population decline and ageing are inevitable, but the severity of these trends will strongly depend on the number of net migrants. Should they be as few as hypothesized by the UN, Elon Musk’s prophecy might be very close to being fulfilled. If Eurostat’s predictions are more accurate, things will be different.

If the Italian economy does badly, Italy may be unattractive for immigrants, as in the last decade (see again Figure 1). However, if the post-COVID-19 recovery continues to be robust, a new strong wave of immigration is possible, as in the first decade of the century before the Great Recession, when they totalled around 300-350,000 per year.

The structure of the Italian labour market has not changed significantly in recent years, with a relatively high proportion of unskilled jobs, that natives are (and will be) unwilling to do. Entering and leaving Italy will probably continue to be relatively easy, because the (formally strict) laws against illegal immigration are only loosely enforced. Businesses need more workers than locals can offer, and the push factor from poor countries will remain strong for decades (Colombo and Dalla-Zuanna 2019). It therefore seems reasonable to predict that immigration will continue to be strong in the coming decades. As a consequence, as Mark Twain would put it, the reports of death (of the Italian population) are greatly exaggerated.

References

- ISTAT (2022). Previsioni della popolazione residente e delle famiglie 2021 con base 1/1/2021, Collana Statistiche Report, 22 settembre 2022.

- Eurostat, Directorate F: Social statistics, Unit F-2: Population and migration (2020). methodology of the Eurostat population projections 2019–based (EUROPOP2019), Technical Note ESTAT/F-2/GL, 30 April 2020.

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2022). World Population Prospects 2022: Methodology of the United Nation – Methodology of the United Nations population estimates and projections. UN DESA/POP/2022/TR/NO. 4.

- Colombo, A. and Dalla Zuanna, G. (2019) “Migrations Italian Style, 1977-2018”, Population and Development Review, 45, 3, 585-615.

No comments:

Post a Comment