A Former National Archives Official Explains Why

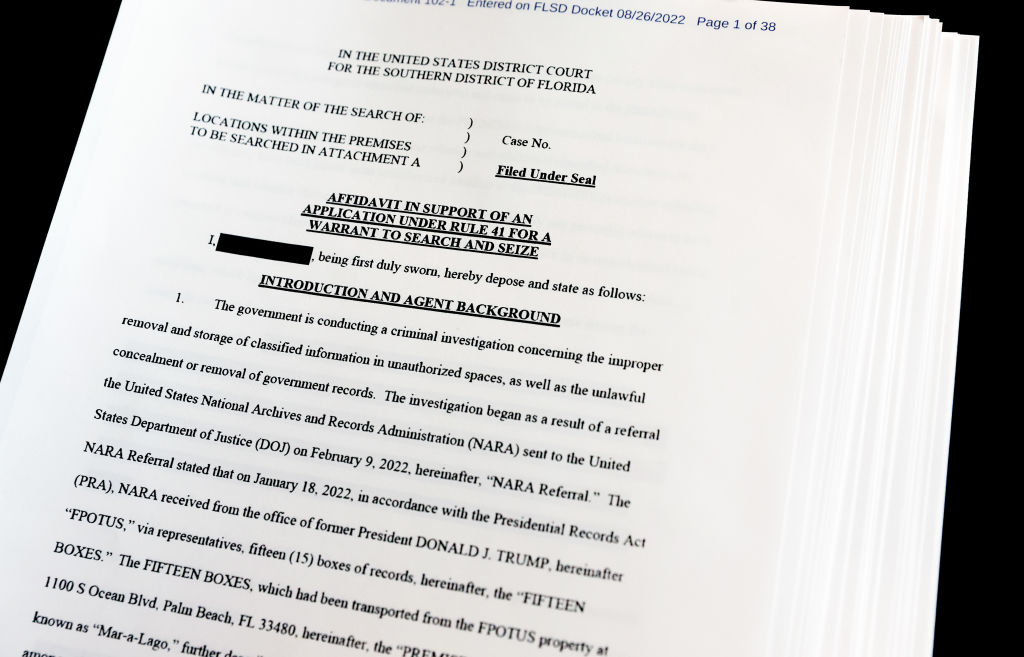

In this photo illustration, pages are viewed from the government’s released version of the F.B.I. search warrant affidavit for former President Donald Trump's Mar-a-Lago estate on Aug. 27, 2022.

BY OLIVIA B. WAXMAN

JANUARY 24, 2023 4:40 PM EST

These days it seems as if classified documents are showing up all over the place.

In August of 2022, the FBI raided former President Donald Trump’s residence Mar-a-Lago in Palm Beach, Fla., seizing 11 sets of material marked as classified. Five months later, classified documents dating from President Joe Biden’s vice presidency were discovered in his possession, including a batch inside a locked garage next to a corvette. On Jan. 20, the Department of Justice searched Biden’s Wilmington, Del., home and found more classified documents, the President’s personal attorney confirmed. In light of that incident, Trump’s Vice President Mike Pence sought legal help to handle classified documents found in his own home in Indiana and says he will cooperate with the National Archives to secure them, the Associated Press reported on Tuesday.

While Biden and Trump have caught flack from both sides of the political aisle, and both are being investigated by special counsels appointed by the U.S. Department of Justice, the problem is actually fairly common among those who work in the executive branch, according to J. William Leonard, who served as the Director of the Information Security Oversight Office at the National Archives from 2002-2008, during the Bush/Cheney era. What’s less common, he says, is for offenders to resist returning classified documents. Speaking to TIME, Leonard reflects on how he handled these issues when they came up during his tenure and how he hopes the federal government will pay closer attention to them going forward.

LEONARD: Actually, unfortunately, it’s not all that uncommon. It’s not just even for a presidency. It’s not uncommon in the entire executive branch of the federal government. Those types of things are by no means unusual. They happen. They happen more frequently than most people would imagine. They probably happen more frequently than they should. In the press of everyday business, when you have massive, massive amounts of paper flowing through any office—not just the President’s or the Vice President’s office—but any office in the federal government, it’s not unusual for classified and unclassified to become inadvertently intermingled.

What’s the proper way to handle classified documents?

Under normal circumstances, those documents are kept in a safe and if you want to read the document, you have to unlock the safe, take the document out, and sit at your desk and work with the document. If you go to the restroom or are gonna go out for lunch, what you need to do is then lock that document back up in a safe before you leave the office.

There are situations though, where you secure the area that it’s being worked in. A SCIF, which stands for Sensitive Compartmented Information Facility, is a secure office space built to specific standards with an alarm system in it. The doors will have certified locks. If you work in a facility like that, the classified materials can be left on your desktop. You just turn the alarm on and lock the door behind you. I worked in those kinds of environments most of my career. So you can imagine how classified and unclassified information can become routinely intermingled. It’s almost inevitable that you’ll end up with a security violation.

As a matter of fact, I recall at one point in my career when I had a security violation. I worked in a SCIF, I was going to Williamsburg, Virginia, to give a speech, and my secretary handed me my itinerary. Unbeknownst to my secretary and myself, it had a paperclip inadvertently attached to classified documents. The next day, I had to go out of my way to stop by the Pentagon to make sure that document was properly secured. And I had to report myself to my security officer. It was a security violation, and it was marked on my record. If you have enough of those during your career, at the very least, somebody’s going to talk to you very seriously or it could have an impact on your security clearance.

Unusual. Usually the only ones who resist returning classified information are the ones who have nefarious motives associated with it.

What is your reaction to the publicity about classified documents discovered from Biden’s vice presidency?

Now we have a special counsel investigating what should have been a routine matter. I dare say, if you go to any presidential library, I’m certain that this has happened before. I can’t necessarily tell you when. Things have gotten spun up. The public reaction today is overblown.

Why?

The case of the former President Trump: What should have been a one-day thing became a big cause célèbre because of the resistance, the lack of full disclosure. In the case of Trump, it’s the old adage—the cover up is worse than the crime. It’s only because of that precedent that now this is a cause célèbre for the current president.

Were there any similar examples of classified documents getting mishandled during your tenure as head of information security oversight at the National Archives?

I got into a rather lengthy dispute with the Vice President’s office as to whether or not the Vice President and his staff had to adhere to the terms of the executive order governing classified information. David Addington, Dick Cheney‘s chief of staff, made the representation that from a constitutional perspective, the Vice President is not a member of the executive branch. It facetiously became known as Cheney claiming he was a fourth branch of government. A congressional committee came within one vote of defunding Cheney’s office and his residence unless he complied with the requirements of my office at the time.

How did it end up?

The issue has really never been resolved. It’s an issue that the current attorney general should address directly. And that is a very basic question, whether or not the Vice President and his staff are subject to the requirements of the executive order governing classified information.

There were instances where members of Cheney’s staff were labeling thoroughly unclassified, mostly political types of information, as handle SCI—Sensitive Compartmented Information. That’s the most sensitive classified information. Some poor archivist who comes across this totally made-up marking, on totally un-sensitive non-national-security-related information, is going to delay that information’s release into the public domain. I find it scandalous to label purely unclassified political related information in such a manner to impede its release.

With classified documents in the news so much these days, are there any myths or misconceptions that you find yourself debunking ?

On the one hand, classified national security information is information that ostensibly requires protection in order to ensure that the improper disclosure of information does not somehow harm the nation. Obviously, it’s a critical tool to be used to protect our nation and the American people. The problem is that there is a long history of this critical tool being abused. Sometimes it’s abused for purely bureaucratic reasons. You know, it’s a whole lot easier to stamp things as classified. Nobody gets in trouble for over-classifying information. [But] the mere act of withholding the information can cause harm to the nation. The classic example of that is the President’s daily brief from August 2001 “Bin Laden determined to strike in the U.S.” If that headline—rather than in a Presidential Daily Brief (which only a handful of people in the entire federal government gets to see)—appeared in the New York Times or the Washington Post or what have you, how different history could have been.

No comments:

Post a Comment