A Norwegian register analysis with control for time-constant individual characteristics shows an association between cohabitation and declining use of primary health care for mental diseases. However, the decline largely occurs before cohabitation starts. Transitioning from cohabitation to marriage does not lead to further improvement in mental health.

Background

It is a strong desire for most of us – in periods of life when we are single – to enter a romantic relationship that is based on mutual love and that develops into a consensual union or marriage of persistently high quality. We expect such an intimate relationship to make our life better. However, should we expect the improvement in life quality to include health benefits? Is it possible that the emotional satisfaction derived from a good partnership, or, for example, the care and support provided by a partner in times of need, contribute to better health?

Several studies have shown lower mortality and better health, especially mental health, for the married than the non-married (although the difference may vary with the quality of the relationship), and the mortality gap between marital status groups is increasing strongly in some countries (Kravdal et al. 2018). Recent research has also documented that cohabitants too enjoy some health advantages compared to those who are single, while it is less clear how they fare compared to married couples. Theoretically, one might expect smaller health benefits from cohabitation than from marriage, because cohabitants tend to have lower relationship quality than married couples (which may also be one of their reasons for not marrying), and tend to live more separate lives (Lyngstad et al. 2011; Wiik et al. 2012).

However, patterns reported in the literature typically reflect a combination of causal effects of being married or cohabiting, compared to being single, and so-called selection or confounding. The latter means that people’s resources, health, lifestyle preferences and various other characteristics affect both the chance of forming a union, the type of union that is chosen, and later health and mortality. The magnitude of this selection component depends on the type of statistical analysis that is done, but it is never eliminated completely.

A recent study of within-individual changes in mental health before and after cohabitation or marriage

In a recent study, we focused on how an individual’s annual number of consultations with a general practitioner (GP) for a mental health condition changes over time, before and after entry into cohabitation or marriage (Kravdal et al. 2022). With this kind of analysis, where the situation of the same person is compared before and after an event, all individual and community characteristics that are constant over time and may affect both health and the chance of forming a union are automatically controlled for. This is a fortunate, but rare possibility in research, made possible in our case by existence of the very complete and accurate Norwegian registers covering the entire population. In our analysis of the period 2006–2019, we also took into account age (people tend to be older after cohabitation or marriage than before it), and several other covariates, such as education, income and number of children (although, as it turned out, these covariates had only a limited impact on our main conclusions).

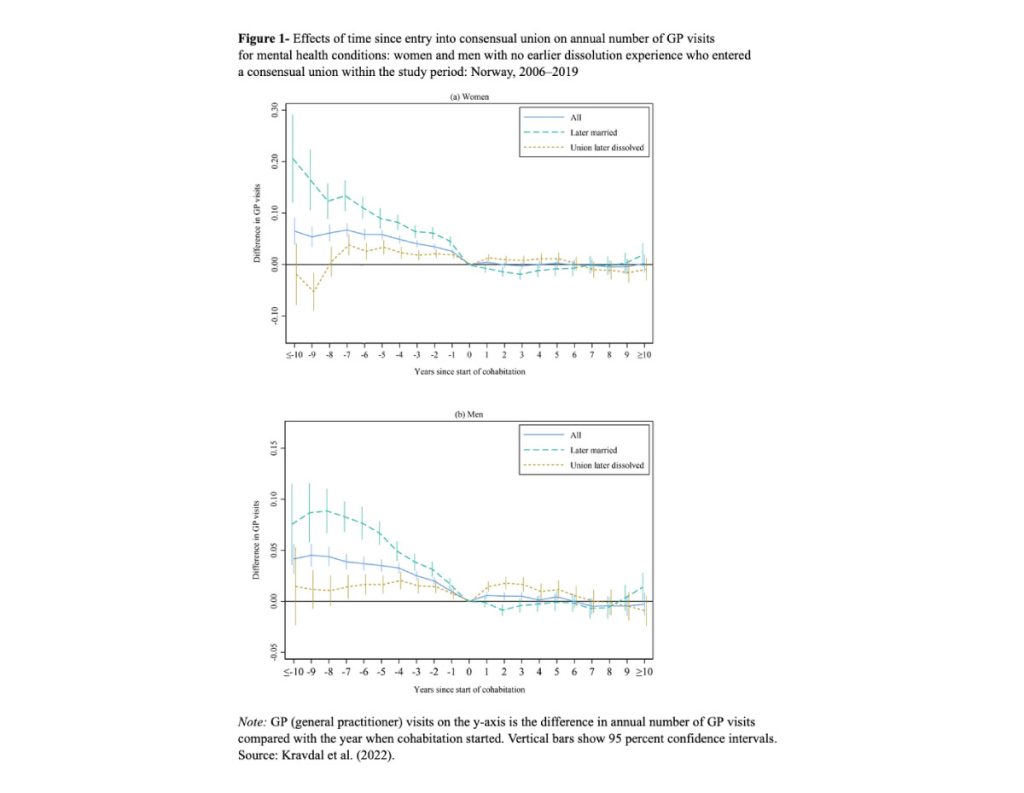

We noticed a decline in GP consultations for mental health conditions for several years before the start of a cohabitation, although there is too much uncertainty in the estimates to be more specific about the timing of the decline (see Figure 1). While trends in use of health care also depend on the (possibly varying) tendency to seek help for health problems, the observed development likely reflects an improvement in mental health during this period. Advantages from being in a romantic relationship are probably key forces behind this improvement. However, one must also be open to the possibility that this and other patterns observed in the data also reflect unobserved characteristics that vary over time and affect both union formation and health, or just effects of health on union formation.

The decline in GP consultations before start of cohabitation is particularly pronounced for those who later marry. More detailed analysis of this group revealed some further decline between the start of cohabitation and marriage, but – interestingly – not after marriage. In fact, among cohabitants who married after, for example, four years of cohabitation, the development over the next decade was not more favourable than among those still cohabiting at that time, despite the higher chance of dissolution among the latter.

To summarize, starting cohabitation does in itself improve mental health. Most of the improvement has already taken place by then. Also, formalizing the union by marrying does not have any impact. However, marriage is a marker of a relatively favourable earlier improvement in mental health.

Among couples marrying directly, who are increasingly uncommon in Norway, mental health improves more before marriage – especially over the last pre-marital years – than among those who marry after cohabitation, and also improves for a few years afterwards (not shown in the figure). This may partly reflect the fact that couples who marry directly have been together for a relatively short period at the time of marriage – and then experience mental health benefits of their relationship that prior cohabitants had already experienced when their cohabiting relationship began.

The broader perspective

Although the Norwegian study indicates that mental health improvements are linked primarily to the dating period before a union is formed – and more marginally to union formation or marriage itself – there may, of course, be other health or welfare benefits of these transitions. In other words, when a couple starts cohabiting or cohabitants decide to marry because they think this best serves their interests, they may well be right in their expectation. It should also be noted that the effects of union formation may differ across countries, and that other patterns may be observed in societies with larger legal differences between cohabitation and marriage than in Norway, or with different welfare systems.

References

- Kravdal, Ø., E. Grundy, and K. Keenan (2018). The increasing mortality advantage of the married: The role played by education. Demographic Research 38 (20): 471–512.

- Kravdal, Ø., J. Wörn, and B.A. Reme (2022) The importance of cohabitation and marriage for mental health – a longitudinal analysis. Population Studies, online first

- Lyngstad, T. H., T. Noack, T., and P. A. Tufte. 2011. Pooling of economic resources: A comparison of Norwegian married and cohabiting couples, European Sociological Review 27(5): 624–635.

- Wiik, K. Aa., R. Keizer, and T. Lappegård, T. 2012. Relationship quality in marital and cohabiting unions across Europe, Journal of Marriage and Family 74(3): 389–398.

No comments:

Post a Comment