Most accounts of women in the workforce focus on gender inequality. Ariel Binder1 provides a related, but often-ignored, discussion of inequality between more- and less-educated mothers. Policies that retrigger progress toward gender equality after COVID-19 may also promote equality among women by easing constraints faced by those without college education.

Many researchers have studied women’s progress toward gender equality in the U.S. labor market. These accounts often examine broad-based factors affecting the typical woman relative to the typical man (e.g. Blau and Kahn 2017). However, as the returns to college education have risen and intergenerational mobility has fallen, economic status increasingly depends on education and family background as well as gender (e.g. Chetty et al. 2018).

Rising inequality among mothers, 1970-2017

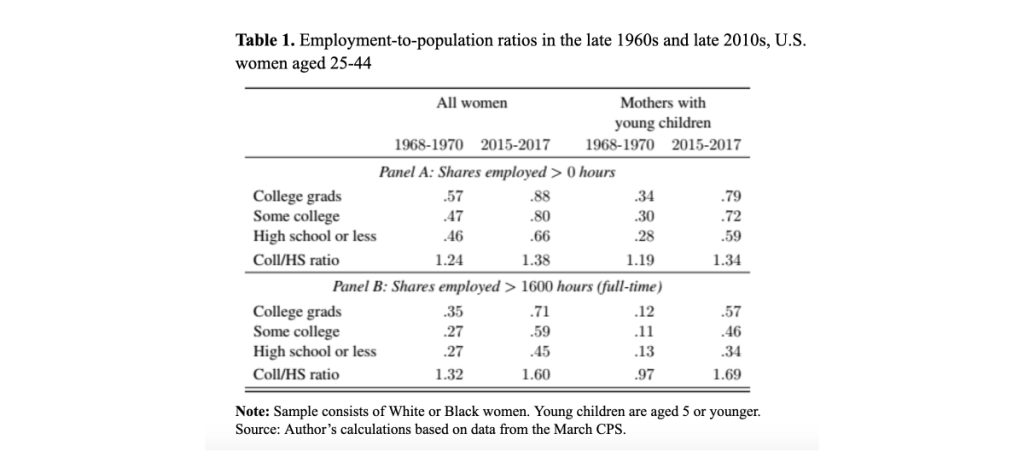

To understand recent progress toward gender equality and its current barriers, it is important to recognize the large within-gender gap in employment that has emerged. Table 1, taken from a recent study focused on mothers (Binder 2021), uses data from the Current Population Survey to illustrate this pattern. In 1970, the shares of mothers with young children employed at all during the year varied little by education status. Between 1970 and 2017, the employed share of college-graduate mothers increased by 45 percentage points, but the employed share of mothers without any college education increased by only 31 percentage points. Overall, the within-gender gap increased from 6 to 20 percentage points.

A larger within-gender gap has emerged when we consider the full-time, full-year (FTFY) definition of employment. (FTFY employment is defined here as working at least 1,600 hours for pay during the year.) This measure is more related to career pursuits and stable lifetime earnings than the previous measure. By this measure, the within-gender gap rose from –1 percentage point in 1970 to 23 percentage points in 2017. Put another way, college-graduate mothers were about as likely as mothers without college education to work full-time in 1970—but they were 1.7 times as likely to work full-time in 2017!

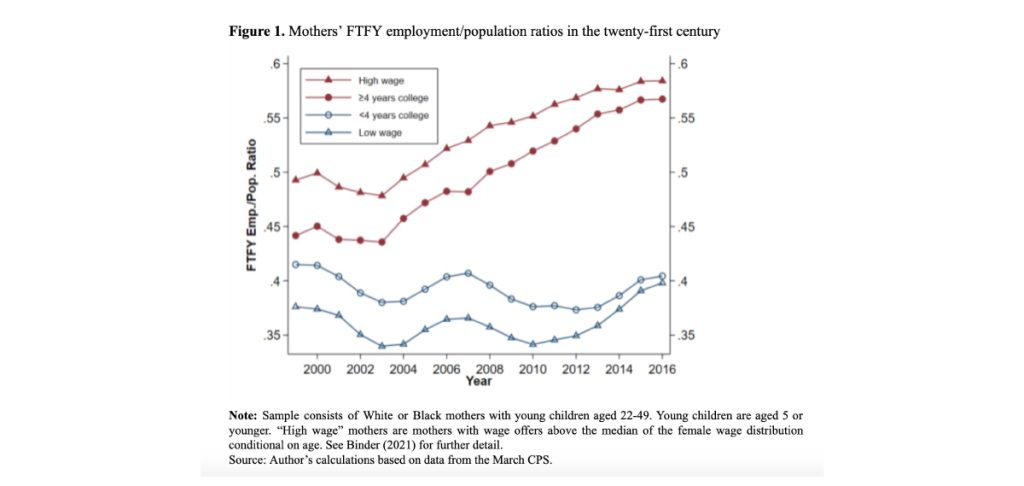

Despite a perception of unchanging gender inequality in the high-skill labor market during the twenty-first century (e.g. Blau and Kahn 2017), Figure 1 shows that the FTFY employment rate of college-graduate mothers actually rose sharply between the early 2000s and 2017. On the other hand, FTFY employment of mothers without college education has stagnated. The same divergence is evident when we consider mothers with above-median versus below-median hourly wages.

Understanding inequality: promotive versus disruptive factors

The rising within-gender gap is a complex phenomenon related to several factors (Binder 2021). Some factors have promoted FTFY employment growth especially for advantaged mothers, while others have disrupted FTFY employment growth especially for disadvantaged mothers.

Contraceptive freedom. The entry of mothers into the full-time workforce in the 1960s through 1980s occurred as oral contraceptives and abortion became widely available to young women, and as the age at childbirth increased. Take-up of oral contraceptives and/or abortion likely raised mothers’ education and employment statuses, but also created a gap between those who did and did not adopt these fertility-control methods.

Employment opportunities. Antidiscrimination laws of the 1960s and 1970s also spurred progress toward gender equality. Thereafter, computer-related technologies greatly changed the labor market and drove up the returns to college education. The combination of these forces disproportionately improved the employment prospects of college-educated mothers and encouraged more women to invest in college education before having children.

Non-wage aspects of work. The United States is notable among advanced economies in its lack of state-mandated paid family leave and other protections for parents and caregivers. The white-collar occupations available to better-educated mothers tend to have more generous health insurance, better retirement savings benefits, greater family leave allowances, flexible work arrangements and more predictable shift-scheduling. These disparities may make full-time work more attractive and feasible for better-educated mothers.

Childcare affordability. The price of childcare has risen dramatically in the past 25 years. Especially for less-educated mothers, the hourly cost of childcare may in some cases equal or exceed the wages they could earn at work. Due to these costs and the often-unpredictable nature of their work schedules, less-educated mothers rely on more sources of informal and “just-in-time” childcare arrangements. In sum, they may face a greater tradeoff between holding a full-time job and securing quality childcare than better-educated mothers.

Family background. Being raised by a working mother is another promotive factor for a mother seeking to balance family and work responsibilities. The rise of inequality in the late-twentieth century has propagated into the twenty-first century due to the transmission of attitudes, expectations, and skills from mothers to daughters (Binder 2021). There is also an interaction between family-level transmission and broader structural forces: the effect of being raised by a working mother on a mother’s own FTFY employment propensity is larger in more-educated families.

Inequality in the time of COVID-19

While previous recessions have disproportionately affected men’s employment, the COVID-19 pandemic has lowered women’s employment and increased gender inequality. Albanesi and Kim (2021) estimated that married mothers experienced roughly a 4.0 greater percentage-point decline in employment between February and April 2020, and a 2.0 point greater decline between February and November 2020 than did comparable fathers. Single mothers also experienced disproportionate employment declines relative to single fathers. Two disruptive factors are behind these developments. First, women are disproportionately employed in the occupations that saw the largest decline in demand due to social distancing measures. Second, the closing of in-person daycare and schooling options created a childcare burden that mothers have disproportionately shouldered. Social distancing has also affected mothers’ access to informal childcare options, such as children’s grandparents. Montes et al. (2021) found that among parents of school-age children, the share of mothers who reported being out of the labor force for caregiving reasons increased by 2.5 percentage points between the last quarter of 2019 and the last quarter of 2020, and the share of fathers by 0.5 percentage points.

How has COVID-19 affected the within-gender gap? The answer is not entirely clear. Initial mitigation measures caused a tremendous loss of jobs in medium- and lower-skill service sectors, disproportionately affecting less-educated women. These sectors have recovered but remain below pre-pandemic levels. In addition, many schools and formal daycares remained fully remote or only offered hybrid learning options through the end of the 2020-2021 school year. Increased childcare burdens have surely affected all sub-groups of mothers. However, as highly-educated mothers were more likely to work full-time before the pandemic, they may have experienced greater and more prolonged work-family conflict. One recent study found greater exits from employment among lower-income mothers (Lim and Zabek 2021), while another emphasized employment decline among college-educated mothers (Heggeness and Suri 2021).

Implications for families and policy

The good news is that the pandemic has ignited discussions to redress structural inequality through policy (beyond short-term measures already taken by governments and employers). Such policy discussions focus on greater leave allowances and benefits, more generous childcare subsidies, more flexible scheduling, and higher minimum wages. There is also debate surrounding the expansion of income-support measures not tied to work. While more generous transfers may cause some low-wage mothers to leave the workforce, there is disagreement regarding the size of this response. Moreover, by easing resource constraints, income transfers may cause these mothers to exit work in the short run to invest in human capital and find a more rewarding occupation. And in the longer run, mothers will invest these extra resources in their children and produce a generation of daughters better positioned to build rewarding careers.

Since 1970, gender inequality has declined as within-gender inequality has risen. Going forward, these two inequalities need not be at odds. Easing mothers’ work-family constraints through labor-market and income-support policies—with the long view of building successful futures for daughters—can both raise the typical woman’s socioeconomic well-being and equalize well-being across women.

1All opinions, interpretations, and errors are the author’s and do not reflect any official position of the U.S. Census Bureau.

References

- Albanesi, Stefania, and Jiyeon Kim. “Effects of the COVID-19 Recession on the US Labor Market: Occupation, Family, and Gender.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 35, no. 3 (August 2021): 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.35.3.3.

- Binder, Ariel J. “Rising Inequality in Mothers’ Employment Statuses: The Role of Intergenerational Transmission.” Demography 58, no. 4 (August 1, 2021): 1223–48. https://doi.org/10.1215/00703370-9398597.

- Blau, Francine D., and Lawrence M. Kahn. “The Gender Wage Gap: Extent, Trends, and Explanations.” Journal of Economic Literature 55, no. 3 (September 2017): 789–865. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.20160995.

- Chetty, Raj, John N. Friedman, Nathaniel Hendren, Maggie R. Jones, and Sonya R. Porter. “The Opportunity Atlas: Mapping the Childhood Roots of Social Mobility.” Working Paper No. 25147: National Bureau of Economic Research, October 2018. https://doi.org/10.3386/w25147.

- Heggeness, Misty L., and Palak Suri. “Telework, Childcare, and Mothers’ Labor Supply.” Working Paper No. 52: Opportunity & Inclusive Growth Institute, November 2021. https://www.minneapolisfed.org:443/research/institute-working-papers/telework-childcare-and-mothers-labor-supply.

- Lim, Katherine, and Mike Zabek. “Women’s Labor Force Exits during COVID-19: Differences by Motherhood, Race, and Ethnicity.” Finance and Economics Discussion Series 2021-067. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, September 2021. https://doi.org/10.17016/FEDS.2021.067.Montes, Joshua, Christopher Smith, and Isabel Leigh. “Caregiving for Children and Parental Labor Force Participation during the Pandemic.” FEDS Notes Series, November 2021. https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-7172.3013

No comments:

Post a Comment