Mobile phones protect women from intimate partner violence (in low- and middle-income countries)

Luca Maria Pesando

In low- and middle-income countries, mobile phones can be viewed as empowering devices for women, says Luca Maria Pesando. Among other advantages, they frequently, although not always, protect women from intimate partner violence.

Information and communication technologies (ICTs) have improved in recent years and are now diffused widely across low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). This massive global social transformation has led scholars and policymakers to increasingly consider the potential of ICTs to empower marginalized communities and improve the lives of economically vulnerable individuals across multiple domains. Among these technologies, mobile phones have played a crucial role.

In LMICs, mobile phones serve a range of functions that may ultimately be associated with improved social development outcomes. With the maturation of the technology and the expansion of mobile data networks, the capabilities of mobile phones have expanded from enabling communication to expanding community outreach, providing rapid information, and delivering remote services (Aker and Mbiti 2010; Pesando and Rotondi 2020). A recent global-level study suggests that the expansion of mobile phones has bolstered sustainable development by narrowing gender inequalities, enhancing contraceptive use, and reducing maternal and child mortality, with biggest payoffs among the poorest countries and communities (Rotondi et al. 2020; Billari et al 2020).

Building on the increasing evidence that mobile phones may serve as vehicle for attaining the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), in a recent paper I examine whether mobile phone ownership is associated with instances of intimate partner violence (IPV) within the household (Pesando 2022). While it is reasonable to expect mobile phones to serve a “protective” role for women by boosting communication, providing access to information, and expanding community outreach (mobile phones as “empowering”), it is also possible that individual phone ownership by women threatens the idea of male dominance within the household and challenges rooted patriarchal norms, in turn resulting into heightened violence on the part of male partners (mobile phones as “disempowering”). I try to reconcile these two views using data from Demographic and Health Surveys from 10 LMICs covering the period 2015-2017 combined with big data from external sources merged at the geospatial level. What I find is that women’s ownership of mobile phones is associated with a 9-12% decreased likelihood of emotional, physical, and sexual violence experienced over the previous 12 months, with robust findings observed across seven out of the 10 countries. Overall (except in specific contexts, such as Angola), mobile phones can be viewed as empowering devices.

Why mobile phones matter for IPV

Social scientists have extensively demonstrated that radio and television have the potential to shape dynamics of gender equality, socioeconomic development, and demographic change by spreading “transformative” content that often transcends national boundaries and ultimately leads to attitude and behavioral change (Jensen and Oster 2009; La Ferrara, Chong, and Duryea 2012). Despite their potential, radio and television are monological sources of information, while mobile phones enable a two-way (dialogical) communication that may affect IPV through many and diverse channels. Among these, mobile phones may affect women’s likelihood of experiencing IPV by streamlining communication, mitigating their sense of isolation from family and non-family members, enabling them to discuss private matters with other women, promoting community outreach and participation, boosting their decision-making power within the household, offering them the opportunity to access reproductive health services remotely (and privately, provided they have sufficient autonomy from their partners) and connect with shelters more swiftly. At a more systemic level, the diffusion of mobile phones may also shape both men’s and women’s attitudes towards women’s roles and responsibilities in society (Varriale et al. 2022).

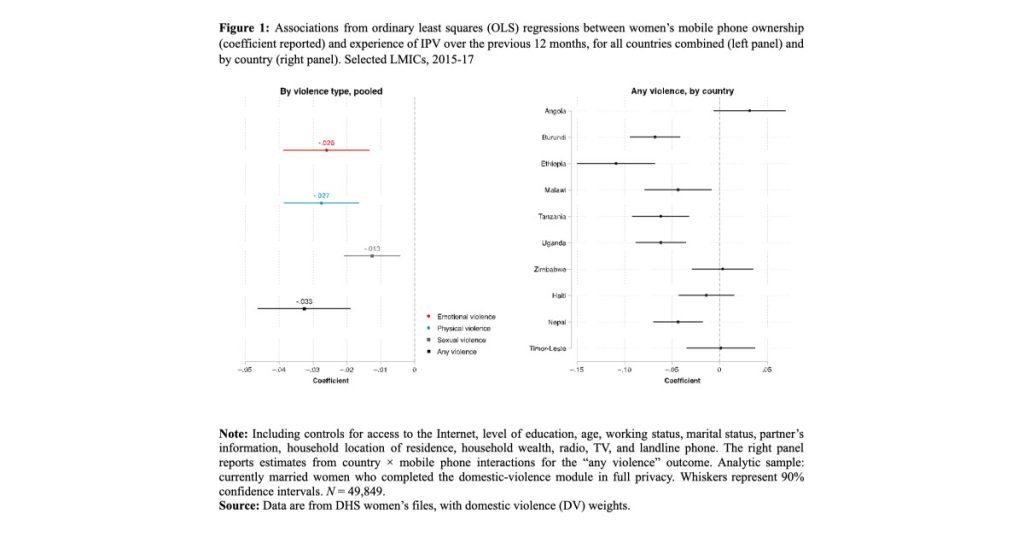

Women’s ownership of mobile phones and IPV over the previous 12 months

Figure 1 (left panel) shows that women owning a mobile phone are 2.6, 2.7, and 1.3 percentage points less likely to have experienced emotional, physical, and sexual violence over the previous 12 months, respectively. In relative terms, these figures correspond to decreases in the range of 9-12%. These findings are observed in seven out of the 10 countries analyzed, are not driven by differences in socioeconomic status between individuals and households, and are also observed at the community level independently of the level of development of the specific community.

The (likely) underlying mechanisms

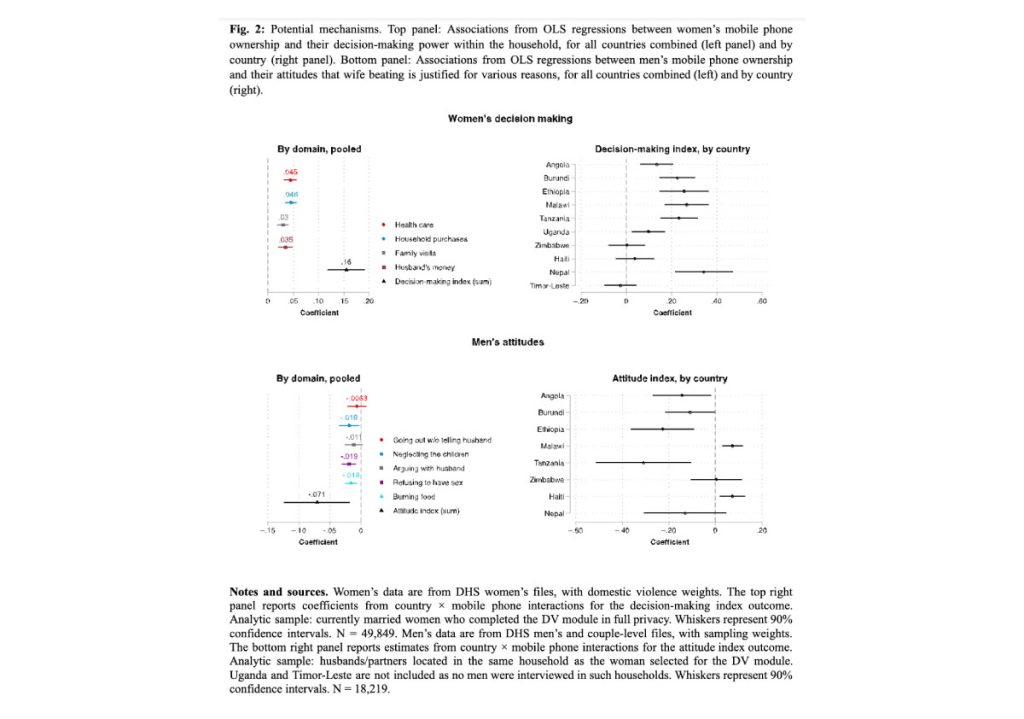

Given the available data, I tested whether, on average, the decision-making power within the household of women owning mobile phones differs from that of women without phones. Also, I investigated whether mobile phone ownership among male partners is associated with favorable or unfavorable attitudes towards IPV. Results are clear-cut and suggest that two mechanisms are consistent with the observed findings:

i) Women owning mobile phones hold, on average, greater decision-making power within the household relative to their counterparts without phones (Figure 2, top panel);

ii) male partners owning mobile phones hold, on average, less favorable attitudes towards IPV relative to their counterparts without phones (Figure 2, bottom panel), suggesting attitudinal shifts towards higher gender equality among male partners owning mobile phones.

Policy implications

Solo female ownership of mobile phones is overwhelmingly associated with lower IPV. The predictive power of mobile phones matters above and beyond socioeconomic progress for explaining variability in women’s IPV outcomes, and mobile phones matter more than radio, television, or landlines. Findings from this study align with other evidence from the African context suggesting that simple SMS-based communication can amplify the participatory features of monological media, creating new spaces for dialogue and public discussion around critical issues, such as IPV (Abreu Lopes and Srinivasan 2014). Mobile phones may constitute a relatively cheap policy lever to attain SDG number 5 (“achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls”). Nonetheless, this can only be an effective policy strategy conditional on broader investments in cheaper, equitable access to technology enabling independent use and ICT (information, communication and technology) skill development, alongside strategies to close digital divides by gender.

These findings may be especially important in the COVID-19 era. During a pandemic that imposes lockdowns and movement restrictions, women and their abusers are bound to share the same space for long periods of time, thus increasing women’s risk of experiencing IPV. In such situations, women with mobile phones might be more likely to report IPV by accessing online services, by joining online forums and networks, or through recently developed mobile apps for help-seeking. The downside of this is that lacking a safe space and facing men who engage in more controlling behaviors, women might find it even more difficult to access individual mobile phone ownership.

References

- Abreu Lopes, C., & Srinivasan, S. (2014). Africa’s voices: Using mobile phones and radio to foster mediated public discussion and to gather public opinions in Africa (CGHR Working Paper No. 9). Cambridge, UK: Centre of Governance and Human Rights.

- Aker, J. C., & Mbiti, I. M. (2010). Mobile phones and economic development in Africa. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 24(3), 207–232.

- Billari, F., Kashyap, R., Pesando, L. M., Rotondi, V., & Trinitapoli, J. (2020) Putting mobile phones in women’s hands spurs sustainable development, Neodemos, https://www.niussp.org/gender-issues/putting-mobile-phones-in-womens-hands-spurs-sustainable-development/

- Jensen, R., & Oster, E. (2009). The power of TV: Cable television and women’s status in India. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124, 1057–1094.

- La Ferrara, E., Chong, A., & Duryea, S. (2012). Soap operas and fertility: Evidence from Brazil. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 4(4), 1–31.

- Pesando L. M. (2022). Safer If Connected? Mobile Technology and Intimate Partner Violence. Demography (online first) https://doi.org/10.1215/00703370-9774978

- Pesando, L. M., & Rotondi, V. (2020). Mobile technology and gender equality. In W. L. Filho, A. M. Azul, L. Brandli, A. L. Salvia, & T. Wall (Eds.), Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals: Gender Equality. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature.

- Rotondi, V., Kashyap, R., Pesando, L. M., Spinelli, S., & Billari, F. C. (2020). Leveraging mobile phones to attain sustainable development. Proceedings of the National Academy of the Sciences, 117, 13413–13420.

- Varriale, C., Pesando, L. M., Kashyap, R., & Rotondi, V. (2022). Mobile phones and attitudes toward women’s participation in politics: Evidence from Africa. Sociology of Development. Advance online publication.

No comments:

Post a Comment