Russia’s invasion of Ukraine inevitably caused a massive flow of refugees towards neighbouring and other EU countries. This movement, as Corrado Bonifazi and Salvatore Strozza show, is closely connected to a pre-existing and already consolidated migration system.

The number of people fleeing the Russian-Ukrainian war has increased very rapidly. At the beginning of the conflict (24 February 2022), the UN High Commissioner Filippo Grandi and other observers ventured an estimate of some 4-5 million refugees. A dire prediction, but reality soon proved even worse.

With an unprecedented act of liberality, surpassing the concessions of the 2015-2016 Syrian refugee crisis, the European Union has granted temporary protection (one year, renewable) within any of its member states to all Ukrainian citizens who request asylum. In this emergency, goodwill on the part of both governments and populations has prevailed, but if numbers continue to increase or the situation lasts for long, or both, organizational problems will soon arise. Compared to other migration inflows, this crisis will probably prove more manageable, however, because political acceptability is much greater now, especially among the countries of the Visegrad Group (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia), traditionally reluctant to relinquish their right to determine who can cross their borders. Moreover, several regions of Ukraine became part of the Soviet Union only at the end of the Second World War; their historical and cultural ties with neighbouring countries are therefore ancient and deeply rooted. Finally, the common socialist past and the widespread fear of Russian expansionism will also very likely fortify solidarity.

Ukraine and the European migration system

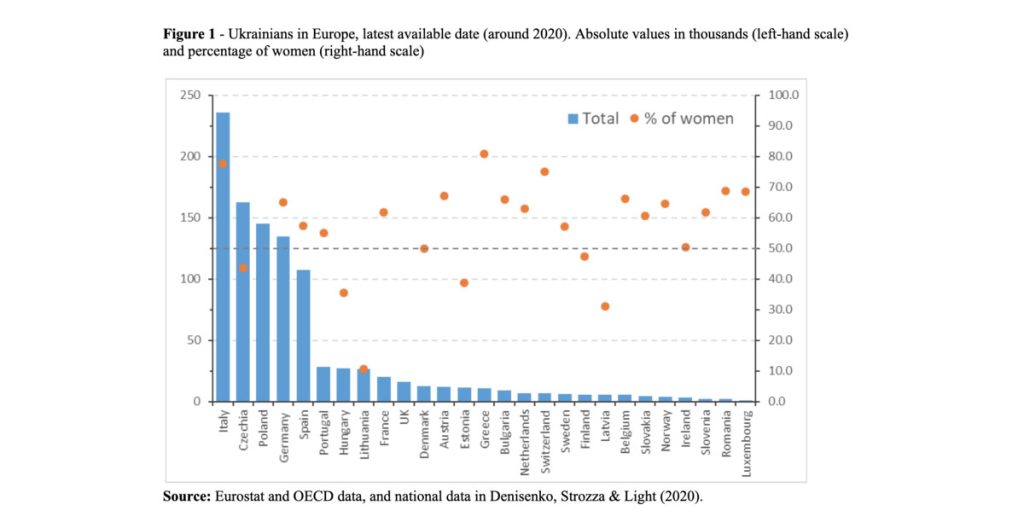

Migration from Ukraine to EU member states is not new, and has gained further momentum since May 2017 when the visa requirement for Ukrainian citizens travelling to the EU for up to 90 days was abolished. According to the latest available data,1 just before the war, just over a million Ukrainian citizens were residing in EU or EFTA countries, mostly in Italy (236,000), the Czech Republic (163,000), Poland (145,000), Germany (135,) and Spain (105,000). As Figure 1 shows, these first five destination countries host 77% of Ukrainian emigrants to the EU.

Ukrainian migrants are predominantly women (up to 81% in Greece and 78% in Italy), with the exception of the Czech Republic (43.7%), Hungary (35.6%) and the Baltic republics (10% to 40%).2Regretfully, no data about gender composition is available for Poland in the sources we used.. These differences reveal distinct migration patterns, with Ukrainian women going mainly to the core countries of the Union, while men usually opt for the eastern European states where incomes are closer to those of Ukraine.

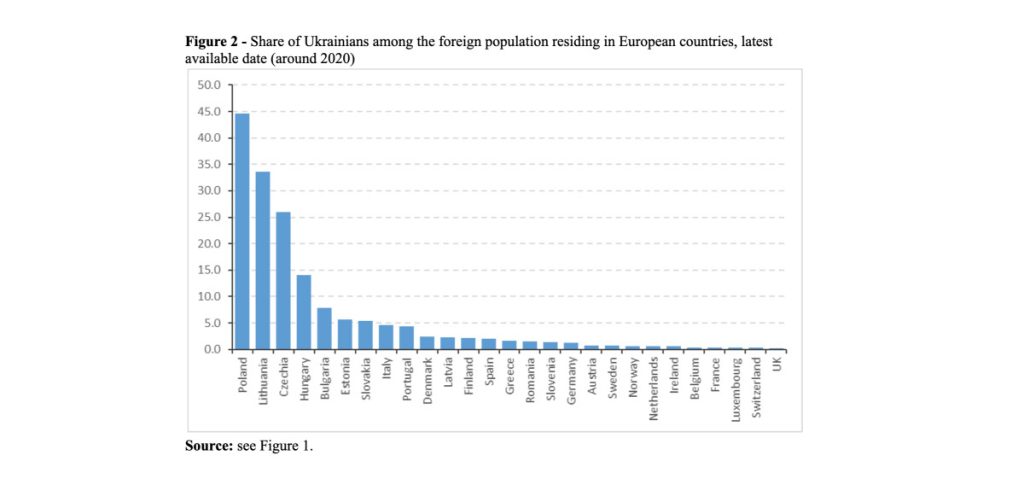

Ukrainian immigration represents an important share of total immigration in the eastern countries of the Union: 45% in Poland, 34% in Lithuania, 26% in the Czech Republic, and 14% in Hungary (Figure 2). In western countries, this share is much lower: 4.6% in Italy and 4.3% in Portugal are the highest figures.

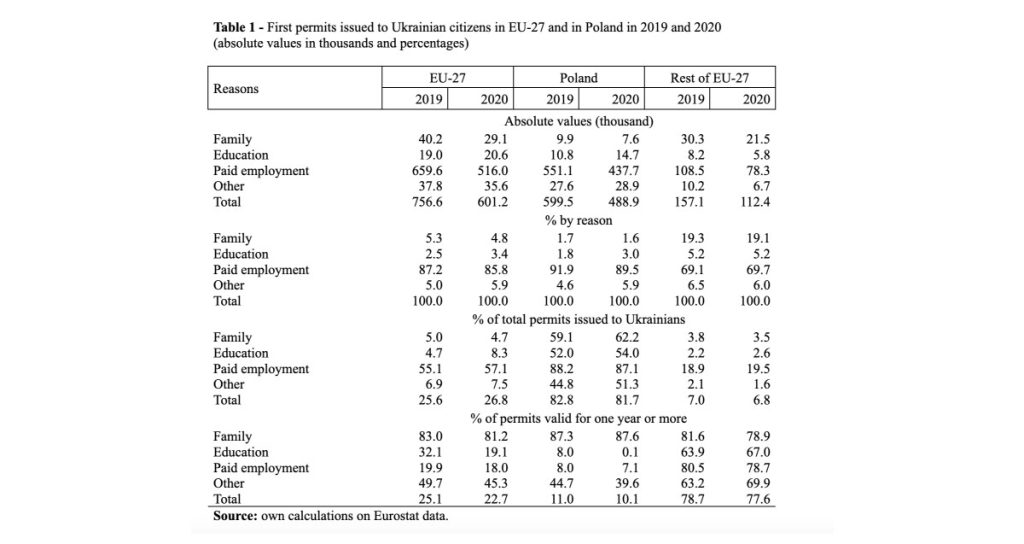

Let us now focus on first residence permits recently granted to Ukrainian citizens in the 27 EU states. While their number declined from 757,000 in 2019 to 601,000 in 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 1), their share of the total increased, rising from 25.6% in 2019 to 26.8% in 2020. Most of these immigrants went to Poland, which granted approximately 80% of all permits to Ukrainian citizens (599,000 and 489,000, respectively, in 2019 and 2020). The share of Ukrainians is also high (between 40% and 60%) in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia and Lithuania. Conversely, among the countries of EU15 it exceeds 10% in Denmark only. Most of these first permits are short-term (less than one year) and are granted for temporary or seasonal activities. Fewer longer-term permits were granted in the EU to Ukrainians in the two years considered (190,000 and 136,000, respectively), once again mainly in Poland (slightly over one-third).

In short, in recent years, migration from Ukraine to the EU has consolidated, giving rise to a relatively large and rapidly increasing diaspora. And it is precisely these emigrants who are now helping to host the massive inflows of Ukrainian refugees, or at least facilitate their arrival.

References

Denisenko, M., Strozza, S., & Light, M. (Eds.). (2020). Migration from the Newly Independent States: 25 Years After the Collapse of the USSR. Springer International Publishing.

This a revised version of an article recently published in Neodemos (in Italian)

No comments:

Post a Comment