OCTOBER 5, 2021

Kyle Harper is the G.T. and Libby Blankenship chair in the History of Liberty at the University of Oklahoma and author of Plagues upon the Earth: Disease and the Course of Human History.

President Thomas Jefferson in 1806 wrote a letter to English physician Edward Jenner. Ten years earlier, Jenner had intentionally infected a boy with cowpox, in order to protect him against the much more terrifying smallpox disease. It worked. Jenner gathered more evidence, and two years later he published his Inquiry into the Variolae vaccinae known as the Cow Pox. News traveled across the Atlantic, and Jefferson was among the first Americans to recognize the revolutionary potential of vaccination. He praised Jenner in lavish terms: “Medicine has never before produced any single improvement of such utility.” In fact, Jefferson foresaw an end to a disease that was then the most deadly and most feared affliction in much of the world. “Future nations will know by history only that the loathsome small-pox has existed and by you has been extirpated.”

Jefferson was visionary—but too optimistic. Mortality from smallpox declined precipitously as vaccination spread, but progress stalled and at times reversed in the late 19th century. Even at the beginning of the 20th century, there were still thousands of cases of smallpox a year in the United States, and not until the late 1920s was the disease completely eradicated from the country. Globally, progress was even more halting. A massive global health crusade in the 1960s and 1970s finally realized Jefferson’s vision of rendering the disease a thing of the past. The last naturally occurring case of smallpox occurred in 1977—171 years after Jefferson’s letter to Jenner imagined a world without the disease.

The example of smallpox elimination is one of many that reminds us the control of infectious disease requires both technical and social adaptations. Jenner’s discovery of vaccination ranks as one of the greatest scientific achievements of all time. But technical solutions on their own are never enough. In the U.S., the spread of vaccination required an effective communication campaign, cultural acceptance of vaccines and, above all, changes in the nature and power of the state. Namely, the rise of public health boards, and their ability to mandate vaccination, were necessary to bring the disease completely to heel domestically.

The COVID-19 pandemic has been a painful reminder that confronting the challenge of infectious disease requires both science and social adaptation. The development of multiple safe and highly effective vaccines against COVID-19 in under a year is a marvelous accomplishment. And yet the combination of vaccine hesitancy at home, and vaccine inequity abroad, has let the pandemic surge anew and linger, with no end in sight. Before COVID-19, the U.S. was ranked high on pandemic preparedness. And yet our response has been an embarrassment and a tragedy—as well as a detailed map of our weaknesses, which our nation’s enemies are sure to be tracking in detail. Our science was ready, but our society was not.

As a historian of infectious disease, who expected that we would face a destabilizing pandemic in our lifetime, I do not find this pattern surprising. But it is concerning that we are not absorbing the lesson. Last month, the Biden Administration released a preview of its future pandemic preparedness plan. The vision is admirably bold. It proposes a $65 billion investment over 10 years that will be managed “with the seriousness of purpose, commitment, and accountability of an Apollo Program.” The plan is motivated by the sober reality that another pandemic is inevitable. Indeed, as the plan states, “There will be an increasing frequency of natural—and possibly human-made—biological threats in the years ahead.” And, as it notes, the next one might well be worse. COVID-19 is a severe and deadly disease, but there is plenty of opportunity for a new pathogen that is equally contagious yet more virulent.

President Joe Biden’s proposed strategy offers much to like. It promises to make major investments in critical areas where we do not do nearly enough, from surveillance and early-warning systems to real-time tracking of viral evolution. It outlines a path towards even more rapid vaccine development and deployment, as well as fundamental improvements in the treatment of viral diseases. It proposes basic improvements in public health infrastructure domestically and globally.

The problem, however, is that nearly all of the agenda focuses on technical solutions. There are only modest hints of an effort to understand how societies respond to the challenge of pandemics and how we can work to make ourselves more resilient. The plan calls for “evidence-based public health communications,” which is laudable, but otherwise there is nothing that matches its scientific aspirations with an equally ambitious call to prepare our society to handle the next threat with greater cohesion and strength. So, two cheers for the Apollo-like vision. But pandemic preparedness is a categorically different project than getting to the moon, because success depends on the behavior of more than 300 million Americans and 8 billion people globally.

It is a disheartening fact that the experience of COVID-19 has rendered our society less ready for the future challenges. The tribalization of our response to masking, vaccines and other mitigation measures has been swift and extreme, and this represents a serious obstacle to preparedness. The reality is that public health is always political. But it is not always bitterly partisan, especially in a polarized society. If anything, we have taken a step backward. Compulsory vaccination, for example, allowed us to conquer smallpox and other menacing diseases, and it became part of our constitutional order and social fabric. In 1905, when a man from Massachusetts protested against a vaccine mandate, saying the requirement violated his individual liberty, the Supreme Court ruled 7-2 that mandatory vaccination was within the power of the states. The majority opinion held that “there are manifold restraints to which every person is necessarily subject for the common good…” On any other basis, organized society could not exist with safety to its members.” Some of the constitutional particularities have changed, but the fundamental issues have not. We are relitigating our sense of the common good, at a time when divisiveness and mistrust are at high tide.

The sooner we grapple with that reality, the better prepared we will be. Evidence-based public health communication is a start, but it is far from adequate. A fully-fledged plan should establish an R&D agenda that draws from the social sciences and humanities; it should put in place the framework, resources and incentives to drive forward our knowledge of the determinants of successful public health initiatives. There is a huge amount of ongoing research that is trying to help us understand why countries (and even states) have responded to COVID-19 so differently. It is already evident what a complex question this presents, involving both apparently fixable variables like good leadership, but also much deeper, historically-rooted cultural factors. A plan to build resilience will have to confront the tensions between individualistic values and social cohesion, the decline of public trust in institutions, the poison of polarization, the role of social media in shaping attitudes toward health and medicine, and the structural inequalities that have been so apparent throughout the pandemic. In short, we need a bold, coherent agenda to advance our understanding of the human side of the equation.

The Biden strategy as proposed earns an A on the technical front, but unless its shortcomings are redressed, it will fail on its social-behavioral agenda. We know all too well how that combination has worked – both throughout history and in our present moment.

President Thomas Jefferson in 1806 wrote a letter to English physician Edward Jenner. Ten years earlier, Jenner had intentionally infected a boy with cowpox, in order to protect him against the much more terrifying smallpox disease. It worked. Jenner gathered more evidence, and two years later he published his Inquiry into the Variolae vaccinae known as the Cow Pox. News traveled across the Atlantic, and Jefferson was among the first Americans to recognize the revolutionary potential of vaccination. He praised Jenner in lavish terms: “Medicine has never before produced any single improvement of such utility.” In fact, Jefferson foresaw an end to a disease that was then the most deadly and most feared affliction in much of the world. “Future nations will know by history only that the loathsome small-pox has existed and by you has been extirpated.”

Jefferson was visionary—but too optimistic. Mortality from smallpox declined precipitously as vaccination spread, but progress stalled and at times reversed in the late 19th century. Even at the beginning of the 20th century, there were still thousands of cases of smallpox a year in the United States, and not until the late 1920s was the disease completely eradicated from the country. Globally, progress was even more halting. A massive global health crusade in the 1960s and 1970s finally realized Jefferson’s vision of rendering the disease a thing of the past. The last naturally occurring case of smallpox occurred in 1977—171 years after Jefferson’s letter to Jenner imagined a world without the disease.

The example of smallpox elimination is one of many that reminds us the control of infectious disease requires both technical and social adaptations. Jenner’s discovery of vaccination ranks as one of the greatest scientific achievements of all time. But technical solutions on their own are never enough. In the U.S., the spread of vaccination required an effective communication campaign, cultural acceptance of vaccines and, above all, changes in the nature and power of the state. Namely, the rise of public health boards, and their ability to mandate vaccination, were necessary to bring the disease completely to heel domestically.

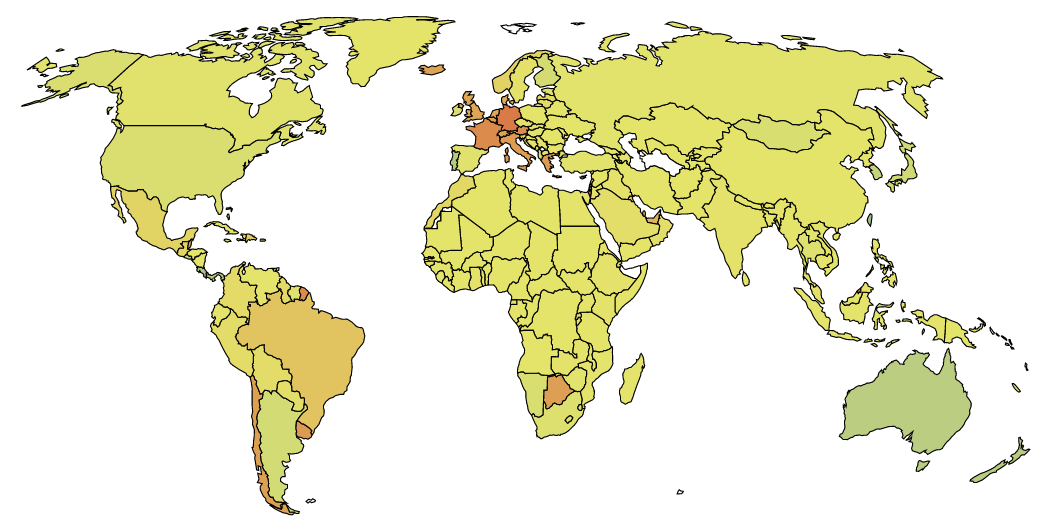

The COVID-19 pandemic has been a painful reminder that confronting the challenge of infectious disease requires both science and social adaptation. The development of multiple safe and highly effective vaccines against COVID-19 in under a year is a marvelous accomplishment. And yet the combination of vaccine hesitancy at home, and vaccine inequity abroad, has let the pandemic surge anew and linger, with no end in sight. Before COVID-19, the U.S. was ranked high on pandemic preparedness. And yet our response has been an embarrassment and a tragedy—as well as a detailed map of our weaknesses, which our nation’s enemies are sure to be tracking in detail. Our science was ready, but our society was not.

As a historian of infectious disease, who expected that we would face a destabilizing pandemic in our lifetime, I do not find this pattern surprising. But it is concerning that we are not absorbing the lesson. Last month, the Biden Administration released a preview of its future pandemic preparedness plan. The vision is admirably bold. It proposes a $65 billion investment over 10 years that will be managed “with the seriousness of purpose, commitment, and accountability of an Apollo Program.” The plan is motivated by the sober reality that another pandemic is inevitable. Indeed, as the plan states, “There will be an increasing frequency of natural—and possibly human-made—biological threats in the years ahead.” And, as it notes, the next one might well be worse. COVID-19 is a severe and deadly disease, but there is plenty of opportunity for a new pathogen that is equally contagious yet more virulent.

President Joe Biden’s proposed strategy offers much to like. It promises to make major investments in critical areas where we do not do nearly enough, from surveillance and early-warning systems to real-time tracking of viral evolution. It outlines a path towards even more rapid vaccine development and deployment, as well as fundamental improvements in the treatment of viral diseases. It proposes basic improvements in public health infrastructure domestically and globally.

The problem, however, is that nearly all of the agenda focuses on technical solutions. There are only modest hints of an effort to understand how societies respond to the challenge of pandemics and how we can work to make ourselves more resilient. The plan calls for “evidence-based public health communications,” which is laudable, but otherwise there is nothing that matches its scientific aspirations with an equally ambitious call to prepare our society to handle the next threat with greater cohesion and strength. So, two cheers for the Apollo-like vision. But pandemic preparedness is a categorically different project than getting to the moon, because success depends on the behavior of more than 300 million Americans and 8 billion people globally.

It is a disheartening fact that the experience of COVID-19 has rendered our society less ready for the future challenges. The tribalization of our response to masking, vaccines and other mitigation measures has been swift and extreme, and this represents a serious obstacle to preparedness. The reality is that public health is always political. But it is not always bitterly partisan, especially in a polarized society. If anything, we have taken a step backward. Compulsory vaccination, for example, allowed us to conquer smallpox and other menacing diseases, and it became part of our constitutional order and social fabric. In 1905, when a man from Massachusetts protested against a vaccine mandate, saying the requirement violated his individual liberty, the Supreme Court ruled 7-2 that mandatory vaccination was within the power of the states. The majority opinion held that “there are manifold restraints to which every person is necessarily subject for the common good…” On any other basis, organized society could not exist with safety to its members.” Some of the constitutional particularities have changed, but the fundamental issues have not. We are relitigating our sense of the common good, at a time when divisiveness and mistrust are at high tide.

The sooner we grapple with that reality, the better prepared we will be. Evidence-based public health communication is a start, but it is far from adequate. A fully-fledged plan should establish an R&D agenda that draws from the social sciences and humanities; it should put in place the framework, resources and incentives to drive forward our knowledge of the determinants of successful public health initiatives. There is a huge amount of ongoing research that is trying to help us understand why countries (and even states) have responded to COVID-19 so differently. It is already evident what a complex question this presents, involving both apparently fixable variables like good leadership, but also much deeper, historically-rooted cultural factors. A plan to build resilience will have to confront the tensions between individualistic values and social cohesion, the decline of public trust in institutions, the poison of polarization, the role of social media in shaping attitudes toward health and medicine, and the structural inequalities that have been so apparent throughout the pandemic. In short, we need a bold, coherent agenda to advance our understanding of the human side of the equation.

The Biden strategy as proposed earns an A on the technical front, but unless its shortcomings are redressed, it will fail on its social-behavioral agenda. We know all too well how that combination has worked – both throughout history and in our present moment.

No comments:

Post a Comment