VARIATION BY GENDER, MARITAL STATUS, AND TIME

Family demographers have long been interested in the debate surrounding changes in the marriage institution, associated with concepts such as the deinstitutionalization of marriage and the Second Demographic Transition. These perspectives focus on alternatives to traditional heterosexual marriage (what can be termed the external context of marriage), such as lifetime singlehood, same-sex marriage, and non-marital cohabitation. In research co-authored with Erik Bond and Ann Beutel, recently published in Demographic Research, we take a different perspective on this debate by focusing on what we term the internal context of marriage, or how social, economic, psychological, and personal dimensions of the marriage experience are perceived by relevant stakeholders (i.e., men and women, comparing those currently married vs. never married).

Using cross-sectional Japanese data from the 1994 National Survey on Work and Family Life and the 2000 and 2009 National Survey of Family and Economic Conditions (NSFEC) (combined N = 8,467), we construct unique measures of this internal context, which we call “marriage counterfactuals”. These measures gauge how people perceive that marriage, or the lack thereof, may have altered their lives.

Why Japan?

Japan is an interesting setting for several reasons. Being the first non-Western country to industrialize, it experienced many of the same economic changes and some similar demographic changes as those in the West (e.g., increasing delays in marriage and rates of lifetime singlehood). However, unlike Western countries, Japan witnessed limited changes in some other social spheres. One notable example here is the family sphere – engagement in alternatives to traditional marriage remains rather culturally limited or legally unavailable (as in the case of same-sex marriage).

Japan is also an interesting setting because it maintains a highly gendered division of household labor within marriage, with men still playing the role of intensive breadwinner and women the role of homemaker. Starting in the 1990s, a time period covered by our data, the Japanese economy experienced a significant downturn and prolonged recession. Ensuing changes in the labor market made it difficult for young men to find suitable employment to realize the breadwinner role.

Because marriage and fertility in Japan are closely related, failure to realize marital intentions is concomitantly linked to failure to meet fertility intentions. Having a fertility rate that is well below replacement level for many decades, and facing the reality of having one of the oldest population age structures in the world has significant implications for Japan’s demographic future. Thus, understanding how relevant stakeholders perceive marriage in Japan’s marriage market (especially during a period of considerable economic change and labor market restructuring) is of considerable interest.

Analytical Strategy for the Study

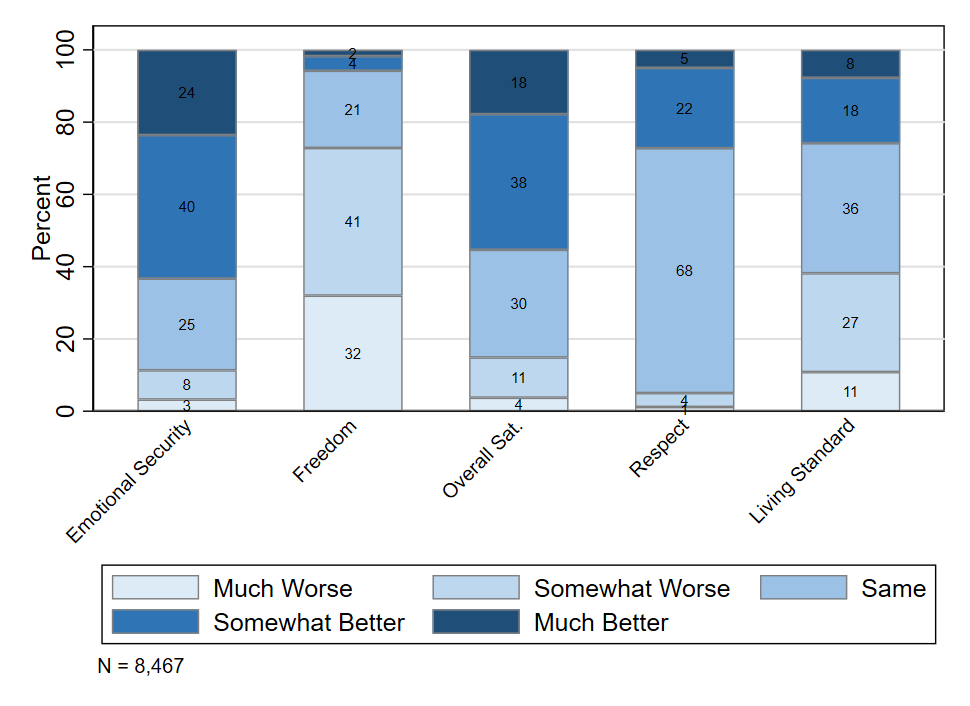

Our sample consisted of people aged 20 to 49. The marriage counterfactual measures used for our study came from a series of survey items that asked respondents to indicate how they perceived that their life would be different (on five dimensions, captured by separate survey items) if they had a marital status that differed from the one they held at the time of the survey. These items concerned change in dimensions such as social respect, emotional security, living standard, freedom, and overall satisfaction. Specifically, married respondents were asked to imagine their life (on the above dimensions) if they had gone unmarried. Non-married respondents, in turn, were to imagine what it would be like to be married. Previously-married respondents were not used in the analysis as they were not asked these questions.

These variables were measured on a 5-point Likert scale, with the following categories: “Much Worse,” “Somewhat Worse,” “Same,” “Somewhat Better,” and “Much Better.” To facilitate the analysis of the pooled data, we coded the variables so that higher values indicate that married life is viewed more as a benefit than single life, and lower values indicate the reverse (that married life is viewed more as a cost than single life). To avoid awkward phrasing, as a shorthand, we use terminology related to the idea of “benefits of marriage” to describe our results.

Findings Related to Marriage Counterfactuals

Figures 1 through 3 show the distribution of marriage counterfactual measures for, respectively, the full sample, by marital status, and by gender.

For the entire sample (Figure 1), as well as across marital statuses and genders, respondents generally perceived ’emotional security’ and ‘overall satisfaction’ as benefits of being married, ‘personal freedom’ as a cost of being married, and ‘respect from others’ as unaffected by marriage. Compared to never-married respondents, currently married respondents were more likely to see ‘living standard’ as a marriage benefit (Figure 2). In comparison to women (Figure 3), men were more apt to view ‘respect’ and ‘emotional security’ as marriage benefits, while women perceived ‘standard of living’ as more of a benefit (consistent with the prevalence of the man-as-breadwinner/woman-as-homemaker household division of labor and the Japanese labor market’s general discriminatory environment toward women).

Figure 1. Distribution of Counterfactual Marriage Measures

Figure 1. Distribution of Counterfactual Marriage Measures Figure 2. Distribution of Marriage Counterfactual Measures by Marital Status

Figure 2. Distribution of Marriage Counterfactual Measures by Marital Status Figure 3. Distribution of Marriage Counterfactual Measures by Gender

Figure 3. Distribution of Marriage Counterfactual Measures by GenderLogistic Regression Analysis

We also conducted a series of ordered logistic regression models to examine the determinants of the marriage counterfactual measures, the dependent variables in our analysis. The main independent variables of interest were measures of gender, marital status, and time period; we also controlled for education, employment status, urban upbringing, and home-ownership. We estimated models for the pooled sample as well as separate models by gender and by marital status. More detailed results are available in the article version of our research.

Our main findings were that perceptions of the marital benefits worsened over time. This is consistent with deteriorating economic conditions and the general assertion that marriage and work/the division of labor are deeply connected in Japanese society. Furthermore, never-married respondents tended to view marriage in more favorable terms than their married counterparts (particularly with regard to freedom and respect from others). Finally, with the exception of the standard of living dimension, men viewed marriage benefits more favorably than women. However, to our surprise considering the man-as-breadwinner role, we find that both men and women viewed marriage benefits less favorably. This may be a result of the general worsening of the marriage market in Japan related to the deteriorating economic situation or to rising income among single women.

Conclusions

Based on our research, we end with four concluding thoughts.

First, despite some dimensions of marriage continuing to be viewed in favorable terms, the key change is that marriage benefits are being viewed less positively over time. In conjunction with other research on family-related attitudes in Japan, this suggests that ideas about marriage there are experiencing substantive change. Thus, it is especially important to consider, as we have, the marital perceptions not only of those who are already married, but also of those who will shape the future of the institution: the not-yet-married.

Second, the internal context of marriage – perceptions of standard of living, respect from others, emotional security, freedom, and overall satisfaction – are important and generally overlooked aspects of the marriage institution. The focus on the external context of marriage and the preoccupation with marriage deinstitutionalization, as well as diversity in family forms, largely ignores these factors, giving an incomplete picture of changes in modern marriage.

Third, gender differences in our analysis make it clear that the traditional division of household labor (i.e., the man-as-breadwinner/woman-as-homemaker model) continues to be influential in Japan.

Fourth, relatedly, in spite of structural changes to the economy and labor market, cultural beliefs regarding traditional marriage persist. We wonder whether this situation will continue or whether, conversely, new partnership forms will begin to gain ground in Japan, a place where such alternatives currently go against the cultural grain.

Authres' Short Bio

Martin Piotrowski is an Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Oklahoma. He received his PhD in sociology from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and was trained at the Carolina Population Center (CPC). His research focuses on aspects of rural-to-urban migration, marriage and fertility, and familial and gender attitudes especially in parts of Asia and most recently parts of Europe. He has done research in several countries including Thailand, Nepal, China, Japan, and Poland and has explored topics involving inter-generational and family relations, household structures, and life course transitions. He has published widely in sociology, family, and demography journals.

Erik Bond is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at Miyazaki International College. He received his PhD in sociology from the University of Oklahoma. His research has focused on marital and gender attitudes in Japan and international-comparative contexts, particularly as they interplay with macro cultural, labor, and policy regimes over time. He has special interest in the use of novel statistical methods for revealing latent values in large data sets. He also works as an LGBTQ+ and diversity advocate in southern Japan.

Ann M. Beutel is an Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Oklahoma. She received her PhD in sociology from the University of Minnesota. Her research has focused on the influence of social location on values, attitudes, and expectations of adolescents and adults and on the relationship between gender and experiences in education and the labor market. She has carried out her research using data from a number of countries, including the United States, Nepal, South Africa, and Japan.

No comments:

Post a Comment