Here's What We Can Learn From the 1918 Flu

How Does a Pandemic End?

|

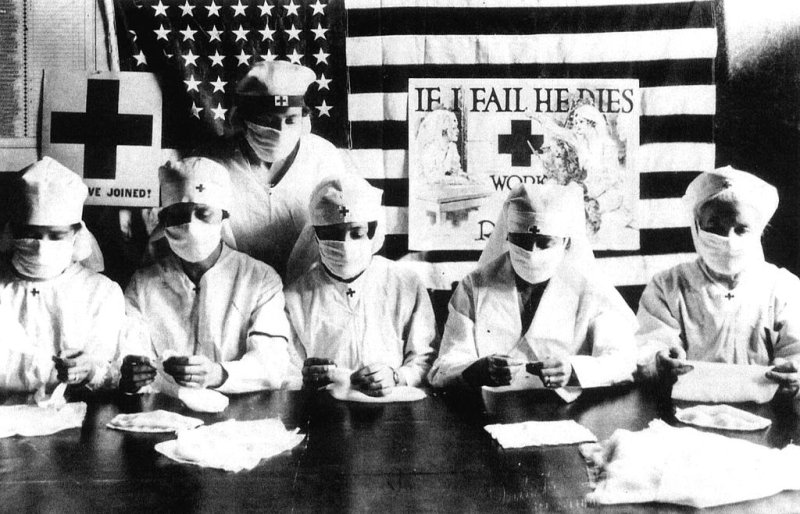

| Red Cross volunteers in the United States, circa 1918. Apic—Getty Images |

BY OLIVIA B. WAXMAN

More than six months after the World Health Organization declaredCOVID-19 a pandemic, as scientific understanding of the novel coronavirus continues to evolve, one question remains decidedly unanswered. How will this pandemic come to an end?

Current scientific understanding is that only a vaccine will put an end to this pandemic, but how we get there remains to be seen. It seems safe to say, however, that some day, somehow, it will end. After all, other viral pandemics have. Take, for example, the flu pandemic of 1918-1919.

That pandemic was the deadliest in the 20th century; it infected about 500 million people and killed at least 50 million, including 675,000 in the United States. And, while scientific knowledge of viruses and vaccine development has advanced significantly since then, the uncertainty felt around the world today would have been familiar a century ago.

Even after that virus died out, it would be years before scientists better understood what happened, and some mystery still remains. Here’s what we do know: in order for a pandemic to end, the disease in question has to reach a point at which it is unable to successfully find enough hosts to catch it and then spread it.

In the case of the 1918 pandemic, the world at first believed that the spread had been stopped by the spring of 1919, but it spiked again in early 1920. As with other flu strains, this flu may have become more active in the winter months because people were spending more time indoors in closer proximity to one another, and because artificial heat and fires dry out skin, and the cracks in the skin in the nose and mouth provide “great entry points for the virus,” explains Howard Markel, physician and director of the Center for the History of Medicine at the University of Michigan.

Flu “does tend to go quiet when the cold weather regresses, but no one knows why,” Markel says.

But, by the middle of 1920, that deadly strain of flu had in fact faded enough that the pandemic was over in many places, even though there was no dramatic or memorable declaration that the end had come.

“The end of the pandemic occurred because the virus circulated around the globe, infecting enough people that the world population no longer had enough susceptible people in order for the strain to become a pandemic once again,” says medical historian J. Alexander Navarro, Markel’s colleague and the Assistant Director of the Center for the History of Medicine. “When you get enough people who get immunity, the infection will slowly die out because it’s harder for the virus to find new susceptible hosts.”

Eventually, with “fewer susceptible people out and about and mingling,” Navarro says, there was nowhere for the virus to go —the “herd immunity” being talked about today. By the end of the pandemic, a whopping third of the world’s population had caught the virus. (At the moment, about half a percent of the global population is known to have been infected with the novel coronavirus.)

The end of the 1918 pandemic wasn’t, however, just the result of so many people catching it that immunity became widespread. Social distancing was also key. Public health advice on curbing the spread of the virus was eerily similar to that of today: citizens were encouraged to stay healthy through campaigns promoting mask-wearing, frequent hand-washing, quarantining and isolating of patients, and the closure of schools, public spaces and non-essential businesses—all steps designed to cut off routes for the virus’ spread.

In fact, a study that Markel and Navarro co-authored, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 2007, found that U.S. cities that implemented more than one of these aforementioned control measures earlier and kept them in place longer had better, less deadly outcomes than cities that implemented fewer of these control measures and did not do so until later.

Public health officials took all of these measures despite not knowing for sure whether they were dealing with a virus or a bacterial infection; the research that proved influenza comes from a virus and not a bacterium didn’t come out until the 1930s. It wasn’t until 2005 that articles in Science and Nature capped off a nearly decade-long process of mapping the genome of the flu strain that caused the 1918 pandemic.

A century later, the world is facing another pandemic caused by a virus, though of a different sort. COVID-19 is caused by a novel coronavirus, not influenza, so scientists are still learning how it behaves. While flu is more active in the winter—and, as Markel points out, the 1918 flu died out in a way “we would expect now” of seasonal flu—COVID-19 was active in the U.S. over the summer. Doctors expect the COVID-19 pandemic won’t really end until there’s both a vaccine and a certain level of exposure in the global population. “We’re not certain,” Markel says, “but we’re pretty darn sure.”

And yet, in the meantime, people can help the effort to limit the impact of the pandemic. A century ago, being proactive about public health saved lives—and it can do so again today.

More than six months after the World Health Organization declaredCOVID-19 a pandemic, as scientific understanding of the novel coronavirus continues to evolve, one question remains decidedly unanswered. How will this pandemic come to an end?

Current scientific understanding is that only a vaccine will put an end to this pandemic, but how we get there remains to be seen. It seems safe to say, however, that some day, somehow, it will end. After all, other viral pandemics have. Take, for example, the flu pandemic of 1918-1919.

That pandemic was the deadliest in the 20th century; it infected about 500 million people and killed at least 50 million, including 675,000 in the United States. And, while scientific knowledge of viruses and vaccine development has advanced significantly since then, the uncertainty felt around the world today would have been familiar a century ago.

Even after that virus died out, it would be years before scientists better understood what happened, and some mystery still remains. Here’s what we do know: in order for a pandemic to end, the disease in question has to reach a point at which it is unable to successfully find enough hosts to catch it and then spread it.

In the case of the 1918 pandemic, the world at first believed that the spread had been stopped by the spring of 1919, but it spiked again in early 1920. As with other flu strains, this flu may have become more active in the winter months because people were spending more time indoors in closer proximity to one another, and because artificial heat and fires dry out skin, and the cracks in the skin in the nose and mouth provide “great entry points for the virus,” explains Howard Markel, physician and director of the Center for the History of Medicine at the University of Michigan.

Flu “does tend to go quiet when the cold weather regresses, but no one knows why,” Markel says.

But, by the middle of 1920, that deadly strain of flu had in fact faded enough that the pandemic was over in many places, even though there was no dramatic or memorable declaration that the end had come.

“The end of the pandemic occurred because the virus circulated around the globe, infecting enough people that the world population no longer had enough susceptible people in order for the strain to become a pandemic once again,” says medical historian J. Alexander Navarro, Markel’s colleague and the Assistant Director of the Center for the History of Medicine. “When you get enough people who get immunity, the infection will slowly die out because it’s harder for the virus to find new susceptible hosts.”

Eventually, with “fewer susceptible people out and about and mingling,” Navarro says, there was nowhere for the virus to go —the “herd immunity” being talked about today. By the end of the pandemic, a whopping third of the world’s population had caught the virus. (At the moment, about half a percent of the global population is known to have been infected with the novel coronavirus.)

The end of the 1918 pandemic wasn’t, however, just the result of so many people catching it that immunity became widespread. Social distancing was also key. Public health advice on curbing the spread of the virus was eerily similar to that of today: citizens were encouraged to stay healthy through campaigns promoting mask-wearing, frequent hand-washing, quarantining and isolating of patients, and the closure of schools, public spaces and non-essential businesses—all steps designed to cut off routes for the virus’ spread.

In fact, a study that Markel and Navarro co-authored, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 2007, found that U.S. cities that implemented more than one of these aforementioned control measures earlier and kept them in place longer had better, less deadly outcomes than cities that implemented fewer of these control measures and did not do so until later.

Public health officials took all of these measures despite not knowing for sure whether they were dealing with a virus or a bacterial infection; the research that proved influenza comes from a virus and not a bacterium didn’t come out until the 1930s. It wasn’t until 2005 that articles in Science and Nature capped off a nearly decade-long process of mapping the genome of the flu strain that caused the 1918 pandemic.

A century later, the world is facing another pandemic caused by a virus, though of a different sort. COVID-19 is caused by a novel coronavirus, not influenza, so scientists are still learning how it behaves. While flu is more active in the winter—and, as Markel points out, the 1918 flu died out in a way “we would expect now” of seasonal flu—COVID-19 was active in the U.S. over the summer. Doctors expect the COVID-19 pandemic won’t really end until there’s both a vaccine and a certain level of exposure in the global population. “We’re not certain,” Markel says, “but we’re pretty darn sure.”

And yet, in the meantime, people can help the effort to limit the impact of the pandemic. A century ago, being proactive about public health saved lives—and it can do so again today.

No comments:

Post a Comment