найдено по ссылке Рэнди.

Любопытное, но совсем небес спорное исследование, пока не могу догадаться: как оно сделано, и является ли предлагаемое вычисление доказательством. Пока видно, что экономистам хорошо преподают математику, и они суют её везде, доказывая совершенно абсуодные, временами, вещи.

Теория имеет хороший потенциал (в нашей стране), поскольку получается, что демографический переход не автономен (как пытается утверждать Вишневский, но ему никто не верит), не сам по себе, а руководим партией и правительством.

Возвращаясь к АГ: демографический переход ведь тоже не всеми отечественными think tank'ами принят. Часть находится в парадигме кризиса семьи, а тут получается, что кризис управляемый и рукотворный.

By Sujata Gupta NOVEMBER 7, 2019 AT 2:59 PM

During the Middles Ages, decrees from the early Catholic Church triggered a massive transformation in family structure. That shift explains, at least in part, why Western societies today tend to be more individualistic, nonconformist and trusting of strangers compared with other societies, a new study suggests.

The roots of that Western mindset go back roughly 1,500 years when a branch of Christianity that later evolved into the Roman Catholic Church swept across Europe and beyond, report human evolutionary biologist Joseph Henrich and colleagues in the Nov. 8 Science.

Leaders of that branch became obsessed with what they saw as incest, the researchers say and launched a “marriage and family program” that eventually banned marriages between even distant cousins, step-relatives and in-laws. Church policies also encouraged marriage by choice instead of arranged marriages, and small, nuclear households, with couples living separately from extended family members.

Using historical, anthropological and psychological data, Henrich and his colleagues show that the Church’s policies helped unravel the tight, cohesive kin networks that had existed. In places under the Church’s influence, a Western-style mindset has come to dominate, the team says.

“Human psychology and human brains are shaped by the institutions that we experience and the most fundamental of human institutions are our kinships [and] the organization of our families,” says Henrich, of Harvard University. “One particular strand of Christianity … got obsessed with this and altered the direction of European history.”

But behavioral economist David Huffman of the University of Pittsburgh urges caution in interpreting the new results. “I’m pretty convinced that they’re finding these correlations,” he says. “I’m just not fully convinced about the causal story from kinship ties to all these other [psychological] variables.”

Across the globe, much variation exists among different societies’ psychological beliefs and behaviors. But in general, individuals in European countries and other countries of British descent tend to be more individualistic and independent and less conforming and obedient. These societies are often described today as Western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic, or WEIRD for short (SN: 11/18/15). (Henrich coined the acronym in a seminal 2010 study in Behavioral and Brain Sciences).

To understand how that Western mindset might have emerged, Henrich’s team started by mapping the worldwide spread of that branch of Christianity, known as the Western Church, prior to the year 1500, when the marriage program reached its height [ну, практически Продовольственная]. The team then zoomed in on the spread of bishoprics, or church administrative centers, across 440 regions in 36 European countries from 550 to 1500. That spread was mapped alongside exposure to the Eastern Church, which evolved into the Orthodox Church and did not adopt such strong taboos against “incest.” [это бес с порно?]

Next, the researchers assessed how varying levels of exposure to the church and its family policies influenced the strength of community- and family-based institutions. For a qualitative approach, the authors used an existing anthropological and historical database of 1,291 populations observed before industrialization. By honing in on elements of family structure, such as marriages between cousins, habitation patterns and presence or absence of polygamy, the team showed that “kinship” — close ties with an extended clan beyond just immediate family — decreased in areas exposed to the church.

When the researchers zoomed in on rates of marriage between cousins, they found that for every 500 years a country spent under the influence of Western Church, this type of marriage dropped by 91 percent.

Lastly, the scientists evaluated that transformation in family structure alongside changes in psychological beliefs and behaviors. Drawing on existing data sources on 24 psychological metrics, such as individualism, creativity, conformity, honesty and trust, the researchers found that the longer a population was exposed to the Western Church, the higher its individualism, nonconformity, and trust of strangers.

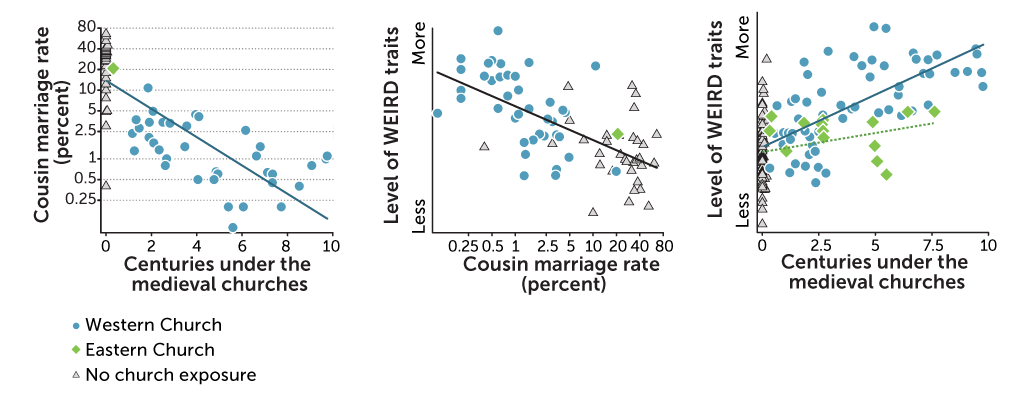

A look at countries categorized by their church experience (dots, diamonds, triangles) suggests that the early Catholic Church’s dissolution of traditional family structures during the Middle Ages reduced marriages between cousins (left). That correlates with intensified individualism, nonconformity and trust of strangers (center), known as WEIRD traits, or those prevalent in Western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic countries. That behavioral shift is weaker in regions exposed to the Eastern Church (right), where taboos against cousins marrying weren’t as strong, researchers find.

J.F. SCHULZ ET AL/SCIENCE 2019

This interplay between history, family structure and psychology affects modern times, the authors say. In Italy, for example, the Western Church’s influence was limited to the northern and central portions of the country until well into the Middle Ages. Data based on Vatican records show that, consequently, marriages between first cousins were almost nonexistent in the north, but accounted for 3.5 to just over 5 percent, on average, of all unions in the far south from 1910 to 1964, the researchers found.

What’s more, the country’s average blood donation rate — a proxy for the trust of strangers — equaled about 28 bags of blood for every 1,000 people, according to data from 1995. But the authors found, for instance, that a doubling of the rate of first-cousin marriages in a given region was linked to a decline in blood donations by about 8 collection bags per 1,000 people, suggesting more distrust of strangers among people there. Similarly, Italians from areas with higher rates of cousin marriages were more likely than other Italians to distrust banking institutions, preferring instead to take loans from family and friends and keep money in cash.

Любопытное, но совсем небес спорное исследование, пока не могу догадаться: как оно сделано, и является ли предлагаемое вычисление доказательством. Пока видно, что экономистам хорошо преподают математику, и они суют её везде, доказывая совершенно абсуодные, временами, вещи.

Теория имеет хороший потенциал (в нашей стране), поскольку получается, что демографический переход не автономен (как пытается утверждать Вишневский, но ему никто не верит), не сам по себе, а руководим партией и правительством.

Возвращаясь к АГ: демографический переход ведь тоже не всеми отечественными think tank'ами принят. Часть находится в парадигме кризиса семьи, а тут получается, что кризис управляемый и рукотворный.

|

| In the Middle Ages, the early Catholic Church banned marriage between even distant relatives. A resulting transformation in family structure partly explains why Westerners today are more individualistic, a study suggests. This illustration shows Henry V, the King of England in the early 1400s, marrying Catherine of France in 1420. |

Early religious decrees transformed families and, in turn, whole societies, a new study says

By Sujata Gupta NOVEMBER 7, 2019 AT 2:59 PM

During the Middles Ages, decrees from the early Catholic Church triggered a massive transformation in family structure. That shift explains, at least in part, why Western societies today tend to be more individualistic, nonconformist and trusting of strangers compared with other societies, a new study suggests.

The roots of that Western mindset go back roughly 1,500 years when a branch of Christianity that later evolved into the Roman Catholic Church swept across Europe and beyond, report human evolutionary biologist Joseph Henrich and colleagues in the Nov. 8 Science.

Leaders of that branch became obsessed with what they saw as incest, the researchers say and launched a “marriage and family program” that eventually banned marriages between even distant cousins, step-relatives and in-laws. Church policies also encouraged marriage by choice instead of arranged marriages, and small, nuclear households, with couples living separately from extended family members.

Using historical, anthropological and psychological data, Henrich and his colleagues show that the Church’s policies helped unravel the tight, cohesive kin networks that had existed. In places under the Church’s influence, a Western-style mindset has come to dominate, the team says.

“Human psychology and human brains are shaped by the institutions that we experience and the most fundamental of human institutions are our kinships [and] the organization of our families,” says Henrich, of Harvard University. “One particular strand of Christianity … got obsessed with this and altered the direction of European history.”

But behavioral economist David Huffman of the University of Pittsburgh urges caution in interpreting the new results. “I’m pretty convinced that they’re finding these correlations,” he says. “I’m just not fully convinced about the causal story from kinship ties to all these other [psychological] variables.”

Across the globe, much variation exists among different societies’ psychological beliefs and behaviors. But in general, individuals in European countries and other countries of British descent tend to be more individualistic and independent and less conforming and obedient. These societies are often described today as Western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic, or WEIRD for short (SN: 11/18/15). (Henrich coined the acronym in a seminal 2010 study in Behavioral and Brain Sciences).

To understand how that Western mindset might have emerged, Henrich’s team started by mapping the worldwide spread of that branch of Christianity, known as the Western Church, prior to the year 1500, when the marriage program reached its height [ну, практически Продовольственная]. The team then zoomed in on the spread of bishoprics, or church administrative centers, across 440 regions in 36 European countries from 550 to 1500. That spread was mapped alongside exposure to the Eastern Church, which evolved into the Orthodox Church and did not adopt such strong taboos against “incest.” [это бес с порно?]

Next, the researchers assessed how varying levels of exposure to the church and its family policies influenced the strength of community- and family-based institutions. For a qualitative approach, the authors used an existing anthropological and historical database of 1,291 populations observed before industrialization. By honing in on elements of family structure, such as marriages between cousins, habitation patterns and presence or absence of polygamy, the team showed that “kinship” — close ties with an extended clan beyond just immediate family — decreased in areas exposed to the church.

When the researchers zoomed in on rates of marriage between cousins, they found that for every 500 years a country spent under the influence of Western Church, this type of marriage dropped by 91 percent.

Lastly, the scientists evaluated that transformation in family structure alongside changes in psychological beliefs and behaviors. Drawing on existing data sources on 24 psychological metrics, such as individualism, creativity, conformity, honesty and trust, the researchers found that the longer a population was exposed to the Western Church, the higher its individualism, nonconformity, and trust of strangers.

Getting churched

A look at countries categorized by their church experience (dots, diamonds, triangles) suggests that the early Catholic Church’s dissolution of traditional family structures during the Middle Ages reduced marriages between cousins (left). That correlates with intensified individualism, nonconformity and trust of strangers (center), known as WEIRD traits, or those prevalent in Western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic countries. That behavioral shift is weaker in regions exposed to the Eastern Church (right), where taboos against cousins marrying weren’t as strong, researchers find.

|

| Medieval church exposure impact on psychology and family structure |

This interplay between history, family structure and psychology affects modern times, the authors say. In Italy, for example, the Western Church’s influence was limited to the northern and central portions of the country until well into the Middle Ages. Data based on Vatican records show that, consequently, marriages between first cousins were almost nonexistent in the north, but accounted for 3.5 to just over 5 percent, on average, of all unions in the far south from 1910 to 1964, the researchers found.

What’s more, the country’s average blood donation rate — a proxy for the trust of strangers — equaled about 28 bags of blood for every 1,000 people, according to data from 1995. But the authors found, for instance, that a doubling of the rate of first-cousin marriages in a given region was linked to a decline in blood donations by about 8 collection bags per 1,000 people, suggesting more distrust of strangers among people there. Similarly, Italians from areas with higher rates of cousin marriages were more likely than other Italians to distrust banking institutions, preferring instead to take loans from family and friends and keep money in cash.

3 comments:

из Гарвардской газеты:

DURING THE PAST 10 years, social scientists have wrestled with a powerful criticism of their research: their favorite subjects, American college students, are often outliers compared to the global population. Economists and psychologists run studies on their students, and then sometimes use those results to make broad claims about human tolerance for risk, moral reasoning, or even the way people perceive lines on a page. But they often are just describing a W.E.I.R.D. subgroup of humanity—Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic—as an influential study calls them. That subgroup represents only 12 percent of the world’s population, but a whopping 96 percent of subjects in psychological studies.

Joseph Henrich, professor of human evolutionary biology (HEB), was lead author on a 2010 paper in Behavioral and Brain Sciences that proposed the WEIRD problem in social science. It has since received more than 5,000 citations, rocking the academic world. Henrich and his colleagues, all then at the University of British Columbia, describe in painstaking detail how WEIRD subjects differ from the global population, arguing for example that risk-averse behavior concerning money might be a recent development local to industrialized areas, rather than intrinsic to human nature. But he avoided any speculation as to why the West had such an unusual psychological makeup.

A paper published today in Science, coauthored by Henrich with Jonathan Schulz and Jonathan Beauchamp, both economists at George Mason University, and Duman Bahrami-Rad, a postdoctoral fellow in HEB’s culture, cognition, and coevolution lab, attempts to explain how Europeans came to be so atypical. In an argument fusing methods from anthropology, psychology, and history, the authors claim that the unusual levels of individualism seen in the West come in part from the emergence of the nuclear family—which is vanishingly rare outside of Europe.

Henrich had long been thinking about how families change the ways that people think. “I was influenced by my ongoing anthropological fieldwork at one of the outer islands of Fiji, where social life is still governed by strong norms of kinship, which endow everyone with a set of responsibilities, obligations, and privileges,” said Henrich in a news conference. “It seemed plausible that kinship systems, or what we call kin-based institutions, might have a big effect on people’s psychology.”

The authors’ argument goes like this. The emergence of agriculture 12,000 years ago favored societies that could work together on big projects, like growing crops. This kind of collaboration required people to be members of tightly bound social networks, strengthened by individuals who showed solidarity with one another. Families in farming societies fostered intense connection among people, because their survival depended on it: extended relatives lived under one roof, polygamy was often allowed, and people married within their own communities and families. Practices like ancestor worship and shared ownership further strengthened these bonds, both in Europe and in many farming societies around the agricultural world.

When the Catholic Church emerged, everything changed. The medieval church in western Europe promulgated unusually strict rules about families: newlyweds were often required to move to a new house, polygamy was weeded out, arranged marriages were discouraged, remarriage was banned, and legal adoption was stopped. Above all, the church harshly condemned incest. People were forbidden to marry their sixth cousins or anyone closer, as well as in-laws and “spiritual relatives” like godparents. Priests and elders would do background checks before the ceremony to uncover any hidden overlap in family trees. The motivations for these new rules are somewhat unclear, but church fathers like Ambrose and Augustine condemned incest in their writings, and various early councils saw it as an affront to God.

“I was surprised just how preoccupied medieval Europe was with the fear of incest,” said Schulz. “Natural disasters such as the plague were attributed to God’s punishment for incest.” When ministers at weddings ask if anyone has an objection to a couple tying the knot, they are drawing on a tradition that was designed to catch incestuous marriages before they happened.

“Interestingly, none of these things can be found in the Bible,” said Henrich at the news conference. “The Western Church bumbled on to a particular combination of taboos and prescriptions and prohibitions.”

The church’s marriage rules resulted in nuclear households, weak family ties, and late marriage, which the authors believe have had deep and lasting psychological impacts on Europeans and their descendants. Unlike the solidarity and conformity that might be favored in earlier agricultural society, Christianized Western Europe favored more individualism. Even though the strict marriage taboos began to loosen in the thirteenth century and the continent has since secularized, the authors thought this lasting change to family structures might explain the peculiar psychology of the WEIRD.

To test this hypothesis, Schulz and colleagues did a massive data analysis. They used medieval documents recording where bishops moved to track the expansion of Catholicism, mapping the length of time that each population in the world has been exposed to the Western Church. They then designed a metric to measure how tightly knit family structures were, including information about cousin marriage rates and whether people lived with extended family. Finally, they made a metric of WEIRDness using current psychological studies and surveys. They found that the more times a population was exposed to the Western Church, the less strong their extended family networks were and the more independence they showed. (The Eastern church had similar but smaller impacts on people.) To make sure this pattern resulted from exposure to the church, the researchers controlled for a large number of variables, including environmental conditions, the presence of medieval universities, and the number of Roman roads through the region.

Even before this new study, some anthropologists have been wary of the possibility of assigning a sense of superiority to the WEIRD. “I worry that W.E.I.R.D. classification flatters the WEIRD, focusing on traits that Westerners typically highlight to describe themselves in ways that are, however inadvertently, pretty self-congratulatory,” wrote anthropologist Greg Downey when the original WEIRD article came out. “If we were to call the same group, Materialist, Young, self-Obsessed, Pleasure-seeking, Isolated, Consumerist, and Sedentary (MYOPICS)… you get the idea.”

This study will surely raise similar objections. In the paper, the WEIRD psychology is associated with “individualism,” “creativity,” “independence,” “analytical thinking,” and trust toward strangers, while the groups with more intense family structures are associated with “conformity,” “obedience,” and “nepotism.” One of the metrics the authors use to measure the amount of socialness a population shows to those outside the immediate community is the number of parking tickets a given country’s United Nations diplomats get in New York City. Because diplomats have immunity from local prosecution, they do not have to pay traffic tickets and can theoretically park wherever they want without punishment. The idea is that the more often a nation’s diplomats take advantage of this privilege—by parking in no-parking zones or fire lanes and not paying the fines, the less “impersonally prosocial” that nation is. All this might feed into a sense of European superiority, based not in biology but in Christian roots.

“We’re not claiming that there’s a better configuration in one kin institution or the other,” said Beauchamp, adding that strong extended families provide a kind of safety net. “We’re just establishing a statistical link here.” Henrich also pointed out that their model explains variation in psychology within Europe.

Anthropologist Jared Diamond ’58, JF ’65, author of Guns, Germs, and Steel, has been criticized by some anthropologists for his “environmental determinism”: the idea that climate and geography determine the success of civilizations. This paper has a much more robust analysis than Diamond’s, but still rests on a single factor: the church. There is a deterministic feel to the work—for example, the authors show that second-generation immigrants to Europe perform differently on psychological tests than the native-born population does, predicted in part by the family structures of their ancestral country.

Attempts to explain the WEIRD won’t stop anytime soon. As one reviewer described the work: “This is the paper that launches a thousand ships.”

Post a Comment