It’s time for the medical community to admit mistakes and stop blaming patients for obesity

Obesity is such an emotionally charged issue in large part because it has become entangled with a person’s willpower and character. This makes it different from almost every other disease due to the unspoken accusation that you did it to yourself.

Many physicians unconsciously engage in fat shaming because they believe that pointing out the many ways a person could’ve done better gives patients extra motivation to lose weight. As if the whole world was not reminding them every single day.

When it comes to fat shaming, I believe the camp that’s popularized the “Calories In, Calories Out” (CICO) mentality are responsible for a share of the blame. I’m talking about physicians and researchers who constantly insist that “a calorie is a calorie” or “it’s all about calories” or “eat less, move more.” What they actually imply with this rhetoric is “it’s all your fault.” Instead of treating the disease of obesity with compassion and understanding, this mentality infuses it with personal shame. I’m here to argue that calories in versus calories out is a pack of lies fed to us by corporate interests.

Obesity has come to be understood as a fundamental imbalance of energy and calories. This is a crucial mistake.If you develop breast cancer, for example, nobody secretly thinks you should have done more to prevent it. Nobody condescendingly tells you to “get with the program.” If you have a heart attack, you don’t face accusations [in the US not in Ru]. Yet obesity has become a disease singularly unique in its association with shame. CICO folks imply that if you could just stop eating and stop being lazy, you too could look like Brad Pitt. But it’s not true. Instead, this deflects the blame for the obesity epidemic from ineffective dietary advice that’s been peddled for decades.

Obesity has come to be understood as a fundamental imbalance of energy and calories. This is a crucial mistake. As I argue in my book The Obesity Code, this obsessive fixation on calories needs to stop.

Up until the 1970s, there was little obesity, and people had virtually no idea how many calories they ate or burned. Yet, without effort, people all around the world lived without obesity.

If the majority of people were able to avoid obesity without counting calories, then how did counting calories become so fundamental to weight stability since 1980? There are two main changes in the American diet since the 1970s. First, we were advised to lower the amount of fat in our diet and increase the amount of carbohydrates. The push to eat more white bread and pasta turned out not to be particularly slimming. But there’s also another problem that largely flew under the radar: the increase in meal frequency.

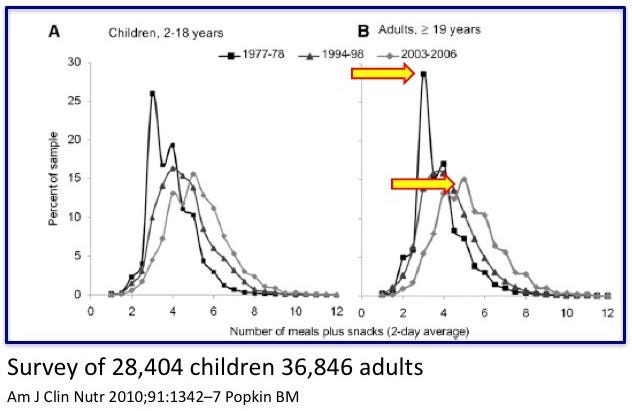

In the 1970s, people typically ate three times per day: breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

By 2004, the number of meals eaten per day had increased closer to six per day—almost double. Now, snacking was not just an indulgence, it was encouraged as a healthy behavior. Meal skipping was heavily frowned upon.

The admonishments against meal skipping were especially loud. Doctors and dietitians told patients to never ever skip a meal. Yet from a physiological standpoint, if you don’t eat, your body will burn some body fat to get the energy it needs. That’s all that happens. It’s the entire purpose the body carries fat in the first place. We store fat so we can use it. If we don’t eat, our bodies use the body fat.

As people gained more weight, the calls for people to eat more and more frequently grew louder. Doctors would say to cut calories and eat constantly—graze, like a dairy cow in a pasture.

People with obesity are victims of poor advice to eat more often and lower dietary fat in a desperate effort to reduce caloric intake.But the advice didn’t work. Either the dietary advice for weight loss was bad, or the advice was good, but the person was not following it. I believe that the former is correct. Therefore, people with obesity are victims of poor advice to eat more often and lower dietary fat in a desperate effort to reduce caloric intake. Their weight problems are a symptom of a failure to understand the disease of obesity. I do not believe they have low willpower or weak character. Many physicians and researchers believe the latter conclusion. They believe the problem is the patients. But that conclusion suggests that the obesity epidemic is the result of a worldwide collective simultaneous loss of willpower and character. Was this obesity crisis actually a crisis of weak willpower?

Somewhere around 40 percent of the U.S. adult population is classified as obese and 70 percent are overweight or obese. Suppose a teacher has a class of 100 children. If one student fails, that may certainly be the child’s fault. Perhaps they didn’t study. But if 70 children are failing, then is it not more likely the teacher’s fault? In obesity medicine, the problem was never with the patient. The problem was the faulty dietary advice patients were given.

This is why obesity is not only a disease with dire health consequences but a disease that comes with a lot of shame. People blame themselves because everybody tells them it is their fault. Nutritional authorities throw around the euphemism “personal responsibility.” But it’s not.

The real problem is an underlying assumption that obesity is all about calories eaten versus calories burned. The natural conclusion of this line of thinking is that if you are obese, “it’s your fault” and you “let yourself go.” You either failed to control your eating or did not exercise enough. But obesity is not a disorder of too many calories. I argue it’s a hormonal imbalance of hyperinsulinemia. Cutting calories when the problem is insulin is not going to work.

Not only do people with weight problems suffer all the physical health issues—type 2 diabetes, joint problems, etc.—but they’re also shamed for it. It’s time for the medical community to admit its mistakes and stop playing the patient blame game.

No comments:

Post a Comment