связь переменилась: выше образование = больше детей, но в США

там и образование гарантирует (высокий) доход, что в РФ совсем не очевидно

Любопытно, что чувак из РЭШ (где Р=РФ), а изучает США:

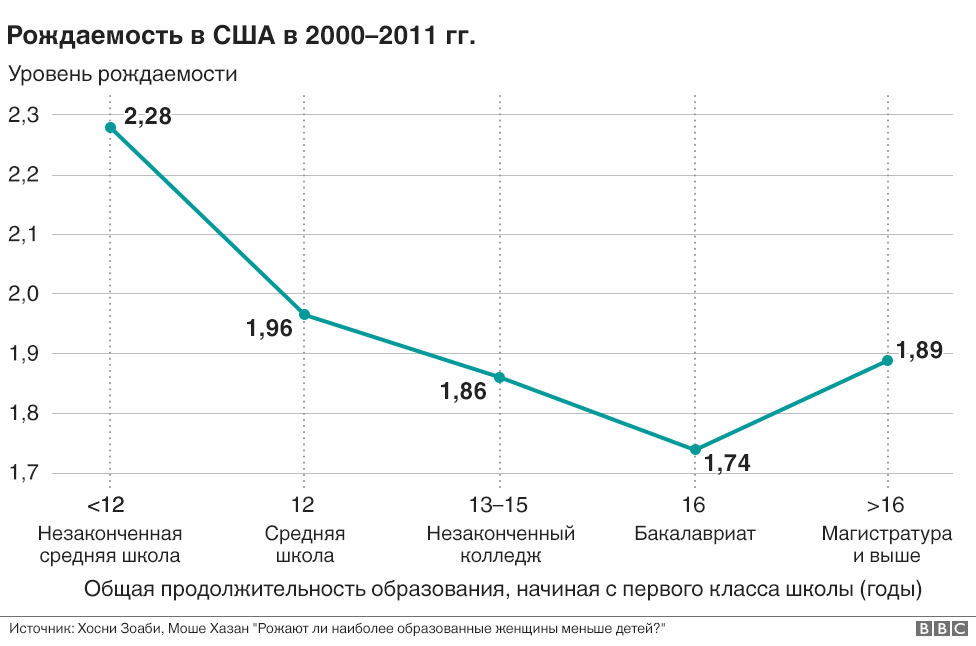

В статье, которая вышла в издании "Economic Journal" в 2015 году, мы с соавтором Моше Хазаном из Университета Тель-Авива исследовали связь между образованием женщин и рождаемостью. И мы выяснили, что начиная с 2000 года эта связь больше не обратно пропорциональна, как считалось раньше. График превратился из нисходящей прямой в U-линию.

про дробнозди на бебеси

upg: ищу,пока только это и это

но нашол

там и образование гарантирует (высокий) доход, что в РФ совсем не очевидно

Любопытно, что чувак из РЭШ (где Р=РФ), а изучает США:

В статье, которая вышла в издании "Economic Journal" в 2015 году, мы с соавтором Моше Хазаном из Университета Тель-Авива исследовали связь между образованием женщин и рождаемостью. И мы выяснили, что начиная с 2000 года эта связь больше не обратно пропорциональна, как считалось раньше. График превратился из нисходящей прямой в U-линию.

про дробнозди на бебеси

upg: ищу,пока только это и это

но нашол

6 comments:

HIGHLY EDUCATED AMERICAN WOMEN NO LONGER HAVE FEWER KIDS

Published Date: October 2014

Since the turn of the millennium, highly educated women in the United States have had higher fertility rates than women with intermediate levels of education. What’s more, while fertility among American women with some college education has been nearly stagnant over the last 30 years, fertility among women with advanced degrees has increased by 0.7 children or more than 50%. These are the central findings of research by Moshe Hazan and Hosny Zoabi, forthcoming in the Economic Journal.

Highly educated women have always had fewer children, but the new study finds that while this was true in the United States until the 1990s, it is no longer true today. What can explain the rise in fertility among highly educated women during a period that saw the largest increase in women’s labour supply?

The researchers argue that the growing divide between rich and poor in American society has created two groups of women: one who can afford to buy services that help them raise their children and run their homes; and another who are willing to supply these services cheaply. For women with college and advanced degrees, the labour cost in the childcare industry relative to their own wage decreased by 10% and 16%, respectively, over the past 30 years. This change accounts for about one-third of the increase in the fertility of highly educated women.

Other commentators might suggest alternative explanations. For example, perhaps there has been a rise in fertility because partners of highly educated women share more of the burden of raising children compared with partners of less educated women. Or perhaps highly educated women are benefitting from recent advances in ‘assisted reproductive technology’ (ART), which enable them to spend long years at university without reducing their chances of future parenthood.

But the new study shows that these alternatives explain only a very small amount of the increase, if any. For example, partners of college graduate women spend only 30 minutes per week more with their children compared with partners of women with lesser education. And partners of women with advanced degrees spend less time with their children compared with those married to women with a college degree, even though women with advanced degrees have higher fertility rates.

Similarly, ART accounts for less than 1% of births in the 2000s. What’s more, comparing 15 US states with infertility insurance laws and the remaining states, which do not have such coverage, shows no difference in fertility rates during the 2000s.

The results of the new study have several implications. For public policy, they highlight potential benefits from pro-immigration policies. Unskilled immigrants can potentially have a positive effect on fertility by increasing the supply of cheap home production substitutes. For many developed countries, which are facing the challenges of an ageing and shrinking population, this may be something to consider.

There are also potential consequences for economic growth. Given the strong correlation between parents’ education and children’s education, an increase in the relative representation of children coming from highly educated families means that the next generation is going to be relatively more educated. This is good news for growth.

ENDS

Notes for editors: ‘Do Highly Educated Women Choose Smaller Families?’ by Moshe Hazan and Hosny Zoabi is forthcoming in the Economic Journal.

Moshe Hazan is at Tel Aviv University. Hosny Zoabi is at the New Economic School.

For further information: contact Moshe Hazan on +972-54-583-8654 (mobile), +972-3-640-5824 (office) or email: moshehaz@post.tau.ac.il; Hosny Zoabi via email: Hosny.Zoabi@gmail.com; or Romesh Vaitilingam on +44-7768-661095 (email: romesh@vaitilingam.com; Twitter: @econromesh).

Проблема неравенства сейчас горячо обсуждается не только экономистами, но и политиками. За последние 30 лет в США оно выросло очень значительно.

Если посмотреть на уровень заработной платы женщин в соотношении с их уровнем образования, то для наиболее обеспеченной группы в 1980 году средний оклад был 24 доллара в час. А в 2000 году это 40 долларов в час - почти в два раза больше. А для наименее обеспеченной группы доходы почти не изменились.

Очевиден дифференцированный рост: богатейшие люди становятся еще богаче, самые бедные остаются в бедности. Так что неравенство выросло.

не богатейшие богаче, а образованные богаче, — какбе из контекста

на сегодняшний день уровень образования женщин в большинстве стран мира выше, чем мужчин.

равные права способствовали экономическому развитию в этот период. Я убежден, что это был ключевой фактор в индустриальной революции.

Если вы помните, в парламенте тогда были только мужчины - у женщин в тот момент не было избирательного права - так что мужчины высказались в поддержку того, чтобы дать женщинам права собственности. И резонно задаться вопросом: почему именно права собственности? Почему не право голосовать, например?

Если ты веришь в равноправие, дайте женщинам возможность голосовать, и затем они сами решат, какие законы им нужны. Логично? Но мужчины решили даровать именно право собственности.

Post a Comment